by alpinac1_pn9him | Dec 30, 2025 | Uncategorized

September 1, 2017

I’m a serial renovator – you know the type, I buy run-down houses, live in it for a bit, fixing up a house I couldn’t otherwise afford. And after about five or 10 years, I sell the house and move on to the next project. What does it have to do with this Alpina? Well, I’m the same with cars.

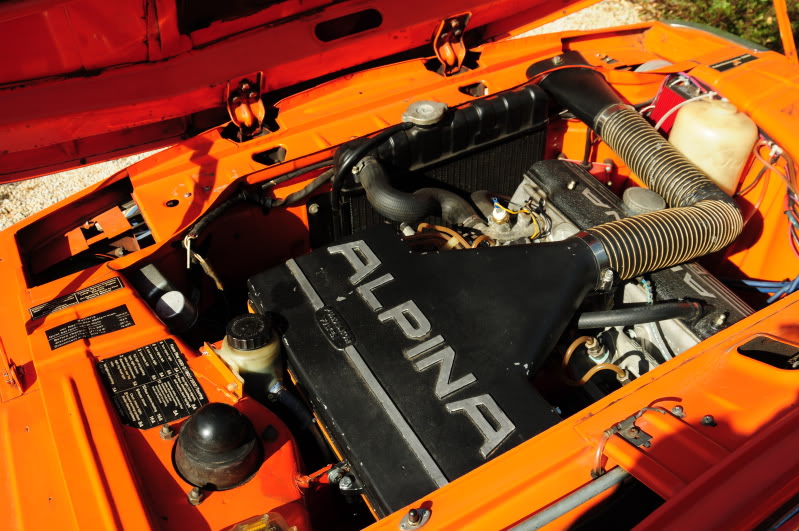

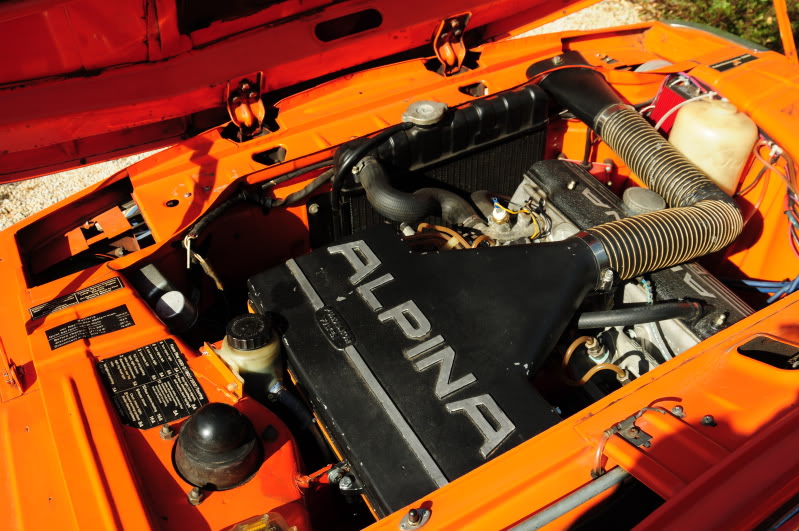

I buy old BMWs, and do a resto-mod, mostly on 2002tiis. I modify them, often with vintage Alpina parts that I had squirreled away over the years. Most recently I built an Inka 2002 touring with virtually every Alpina part available back in the day, including a complete Alpina A4 four-throttle, kugelfischer-based, mechanical fuel injection system (sporting the appropriate personalized plate FAUX A4).

While it’s fun building faux Alpinas, I’ve had a hankering for a real, honest to God Buchloe-built Alpina. For years I’ve been looking for the right car but it’s always alluded me; they either weren’t California legal or a real Alpina. The few that ticked both boxes were too expensive or too much of a project for a shade-tree mechanic like me.

One random morning, while drinking my coffee and reading an email blast from Bring-a-Trailer, I spotted a listing for one of my favorite Alpinas – an e21-based C1 2.3 (https://bringatrailer.com/listing/1982-alpina-c1-2-3/). The pictures weren’t the most revealing, but it looked decent. The interior was pretty much all there but old: disheveled, faded, and cracked. The mechanics looked overly greasy, but were claimed to be in good condition, including new brakes and suspension (with the original Alpina/Bilsteins, ready to be rebuilt). Even from the (deceiving?) pictures on BaT, the car clearly needed someone to lovingly massage it, but didn’t appear to be a basketcase. Could this be the one for me?

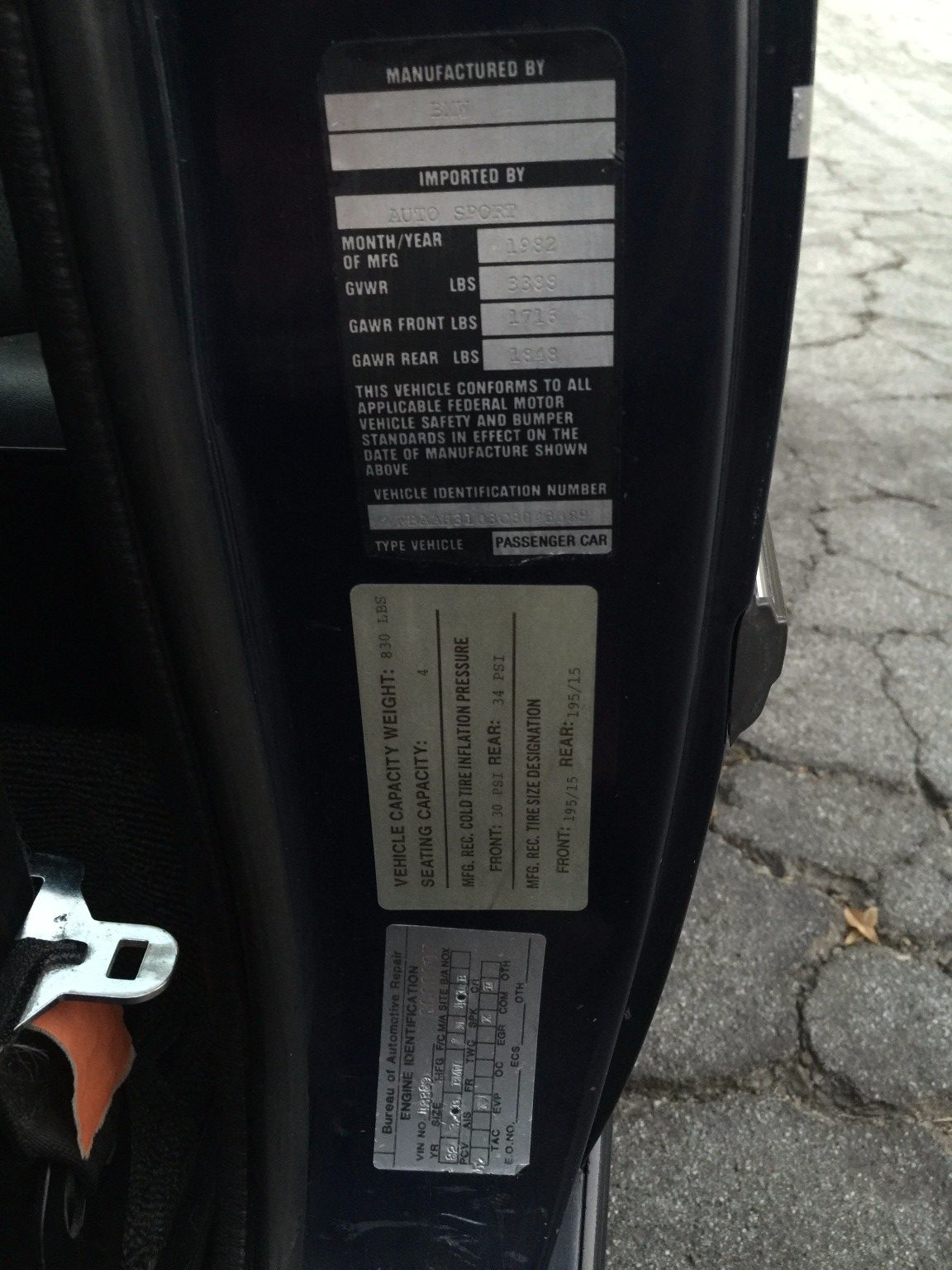

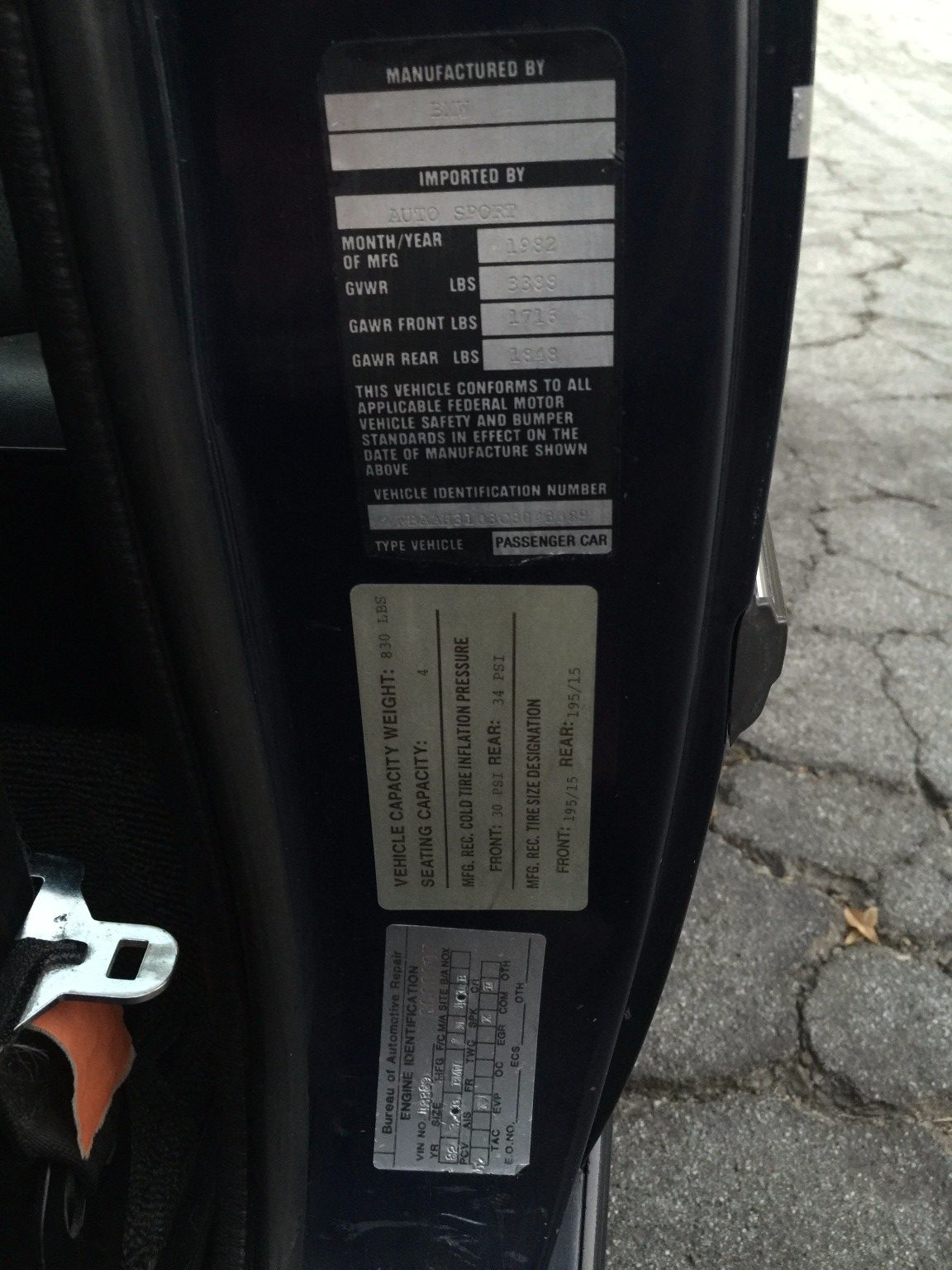

My requirements were that it was registerable in California and a genuine Alpina. Figuring out whether it was California legal was easy. To register a grey-market car (a Euro-market car not imported by BMW of North America) in California, it needs a valid so-called BAR sticker, an indication that the car has been approved by the California Bureau of Automotive Repair and complies with smog requirements at the time the sticker was issued. Cars that have a BAR sticker and have been continuously registered in California since getting the sticker are grandfathered in. If the car moved out of state after getting a sticker, it needs a new sticker if it moves back! Because getting the sticker is an expensive and difficult process, a valid BAR sticker is the holy grail for euro-car fans.

Looking at the pictures on BaT, the car had California plates, looked to be currently registered in California, and had a BAR sticker. I contacted the seller and was able to verify it had been continuously registered in the Golden State and was smog legal. One hurdle cleared!

Next, the most important – and certainly more difficult – hurdle: is it a real Alpina? That may seem like an easy question to answer, but it actually isn’t. Back in the day, it was hard to know if a car was a genuine Alpina or “just” an old BMW with some Alpina parts on it. Even an Alpina dash plaque did not guarantee authenticity – anyone can buy the plaque (available on eBay even now!) and have it properly engraved. Hell, I did that with a gray-market 1980 323i I owned a couple of decades ago. Without paperwork, like a bill of sale with the VIN, it often felt like an act of faith to believe a BMW was a real Alpina. Popular wisdom was that even Alpina did not have records from back in the 70s or 80s and that they were hostile to inquiries.

Reading the comments on the BaT listing, it was clear that several others were on the hunting for some indicia of authenticity. One guy asked the seller to check for the Alpina stamping on the head and block. When the seller didn’t things got nasty; he was accused of trying to pawn off a 323i with a bunch of cool parts as a real-deal Alpina. I chuckled at the outrage, having seen too many so-called Alpinas that couldn’t pass the originality test.

Then a previous owner piped up, claiming it was a real Alpina with an unethical mechanic pilfering many of the unique parts. He provided some interesting history, including the importer, but was largely ignored. And, to make it worse, the seller rose to the bait, engaging with those who cast doubt on the car. An early bidder wondered if he was a fool for jumping out to a $9,000 bid early-on. It seemed other bidders were scared away by the constant cacophony of callous comments, and they thanked the haters for saving them from buying such a questionable car.

One comment politely summarized the mood of the bidders: “Been watching this one with interest and the glaring omission of stamped block and head photos and/or verification from [the Alpina factory in] Buchloe of its authenticity are growing problems for the seller. … Until then I’m in the camp that it’s a 323i with cool parts and would bid accordingly.”

The auction ended with the car not meeting reserve, the highest bid being $10,000 (mine was second highest at $9,600). I bid on the car on the theory that it was worth around $9,500 (to me at least) even if it was “only” a 323i with a bunch of cool Alpina parts and an all-important valid BAR sticker. I could, after all, make another “faux Alpina,” like I did with the Inka touring. And it had a bunch of expensive parts left (ultra rare seats, some suspension components, correct wheels, shift knob and steering wheel) and an Alpina dash plaque – real or not.

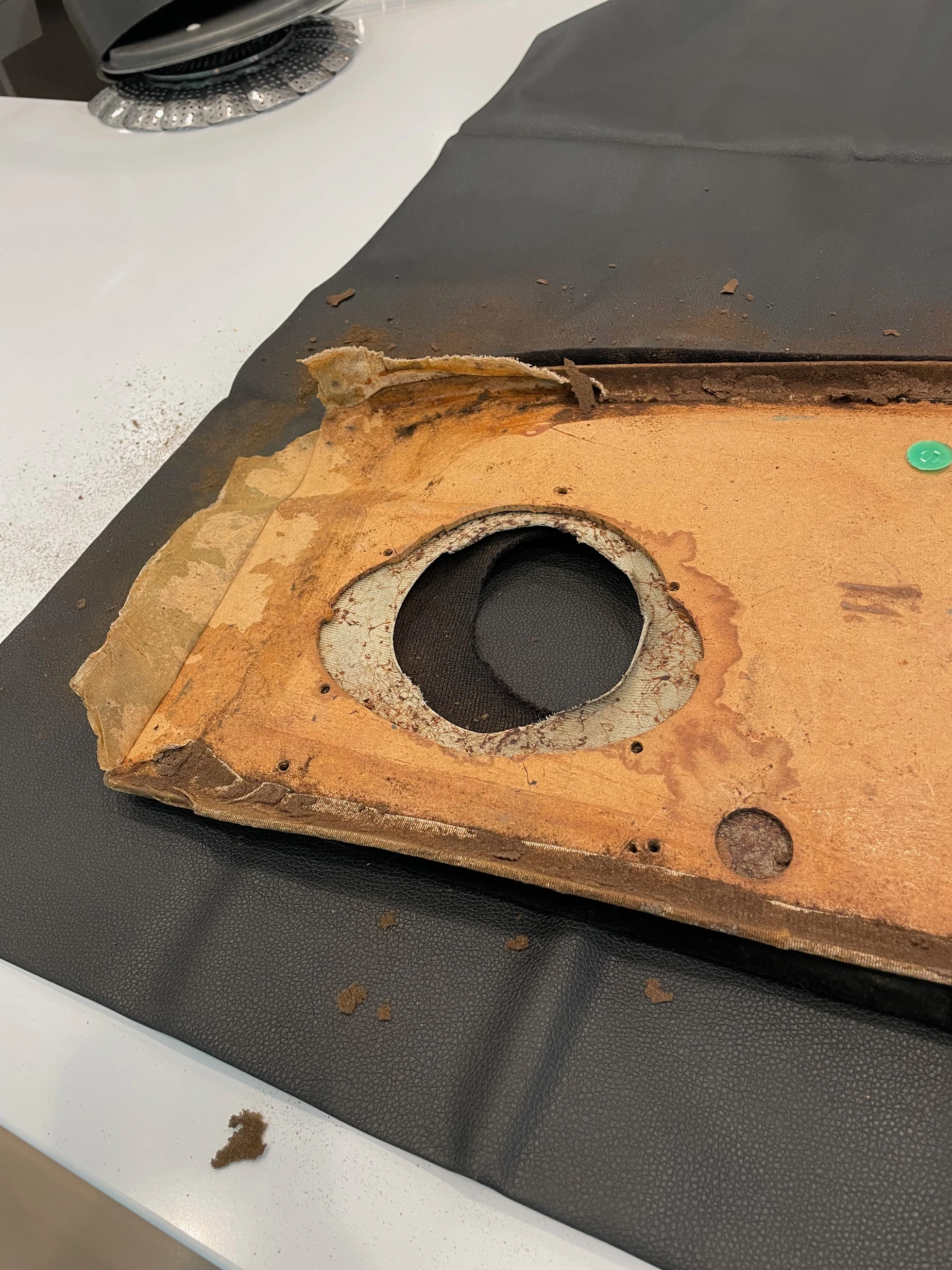

Then two things happened. The first – getting a pre-purchase inspection – almost made me walk away. A few minor and odd flaws were revealed – like the tow hook that is welded to the spare tire well was torn out and the exposed raw metal was rusting – and some other similarly quirky problems that weren’t big deals over all. But there was a big issue: a compression test that revealed low compression in two adjacent cylinders, indicating a blown head gasket – or possibly worse, like a cracked head or bad rings in adjacent cylinders. I wasn’t that worried about an engine rebuild as I’d do everything myself other than the machine work, but the project was getting pretty expensive – especially if all I was getting was a 323i with a bunch of cool Alpina parts and BAR sticker.

While arranging the PPI, I again attempted to sleuth out the car’s history. I talked with the owner, but that offered nothing new. Then I tried to chase down the guy the previous owner said imported the car, Mike Dietel. Mike used to own one of the three Alpina authorized shops in the USA (and had done some really cool home-made conversions in his shop in Orange County). Got nowhere with that. Because I either have too much time on my hands or don’t understand how to prioritize correctly, I kept scrutinizing the pictures, comments, and the seller’s answers on the BaT listing. One of the most critical comments chided the seller for not contacting Alpina to prove it was authentic. But wait, I thought. Decades of conventional wisdom said that Alpina did not have records from back then. And that you needed an “in” there to even have a conversation about cars from the 70s and 80s. Could that conventional wisdom (and my acceptance of it) be wrong? Mr. Critic implied he emailed Alpina and they authenticated a car for him. Frankly, I figured he was blowhard know-it-all, but if he was right…..

I emailed Alpina with the VIN and a day and half later I got a lovely email from Elisabeth Steck in the Automotive Sales division of Alpina: “I have checked and I found the car in February of the year 1982 and we have had it in our company for modification. Hope, this will help you.” Since the car was built in February of 1982, it seems it went directly there from BMW. Eureka! BINGO! Suddenly the car was more than reasonably priced. And, importantly, the right amount of project for me. Eventually, after a bit too much negotiation, it was mine. We arranged shipping, I drove the car to my secure, undisclosed location and have started taking it apart.

So, I now have a new project – this time a real Alpina, with a bunch of genuine Alpina parts. Requiring lots and lots of work to bring it back to its past glory, just the way I like my projects. And I should be ready to sell it in about five or ten years.

by alpinac1_pn9him | Dec 30, 2025 | Uncategorized

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

by alpinac1_pn9him | Nov 24, 2025 | Uncategorized

September 15, 2017

As a bona fide 2002 nut, I spent too much time dreaming of Alpina-modified 02s, the best being the 2002tii version known as an Alpina A4. In addition to the usual suspension and braking upgrades, Alpina was known for their tweaked motors. The standard 2002 had about 100hp, the tii had 130hp, and the Alpina A4 and A4S had 165-180hp, achieved through a four-throttle injection system, a tweaked kugelfischer pump, a 300* motorsport cam, and high compression pistons.

I bought my first A4 injection system in the late 1980s, but never got around to installing it in the 2002tii I had back then. (Ironically, I sold that tii and bought a gray-market 1980 e21 323i.)

In 2002, I bought “Sandy,” a Sahara beige 1973 2002tii with a low mileage Dave Cruise motor and Franz Fechner 5-speed. I installed an Alpina A4 system I had found on eBay.de.

I had fun with that car, but decided I really wanted a 2002 touring. I sold Sandy and bought Inkie, a 1972 Inka touring I imported from Holland.

Although that car was in fine condition, I promptly tore it apart and rebuilt it as an Alpina A4, and it sported the personalized California plates “FAUX A4.”

The motor was the highlight of the rebuild. It had an S14 crank (2.2 liters), 304* schrick cam, custom 10.0:1 JE pistons, an aluminum flywheel, connected to a 5-speed close ratio transmission.

The inka touring got some other special parts too. Underneath, the suspension had very rare Alpina “Green Dot” Bilstein struts up front and inverted rear shocks, Alpina adjustable sway bars, and ST springs for great handling and good ride-height.

The interior featured reupholstered 2002 turbo seats and a Momo Prototipo, the steering wheel used by Alpina.

That car was my daily-driver until it was replaced by a 911.

by alpinac1_pn9him | Nov 24, 2025 | Uncategorized

September 23, 2017

The Alpina has a good friend in the garage with it, a Fjord 1974 2002tii.

It’s my third tii, and my 8th ’02 (Agave 68 1600, badly repainted silver 69 2002, Amazon 74 2002, Pastel 76 2002, Malaga 72 tii, Sahara 73 tii, Inka 73 touring, and the Fjord 74 tii).

The daily driver is — sacrilege! — a Porsche Cayman S. My first new car, ever (my wife bought a new 2008 328it six-speed, our first new car, and I drove that daily when she got a 318ti). It’s the perfect sports car in my mind and since I no longer drive the kids to school (one in college, one taking the bus to high school), I don’t need a back seat. My son hates to be in the car with me because, as he says, “it’s not an old man’s car. It should be driven by someone young, like me.”

He’s probably right, but I don’t care.

by alpinac1_pn9him | Nov 24, 2025 | Uncategorized

October 3, 2017

If you read my first blog entry, Sleuthing the Car (how I found my Alpina), you likely recall the noise about whether the car was “really” an Alpina. That begs the question: What is an Aplina. Its easy to answer for modern cars. After all, Alpina, now, is a bona fide car manufacturer (with their own Vehicle Identification Numbers and VIN plates) and the cars they build are Alpinas. Case closed.

But back before they became a manufacturer in 1983, Alpina was just a BMW tuner, like Dinan is now (and Ruf is for Porsche and AMG was for Mercedes Benz). The parallel to Dinan is striking, as if Dinan modeled heir business after Alpina.. Like Dinan, Alpina back in the day, was the premiere vendor and manufacturer of parts to modify your BMW and builder of BMWs that they modified. And, like Dinan, you could get the modified BMWs directly from Alpina (or Dinan) or you could get a BMW modified by an authorized Alpina (or Dinan) dealer. And, eventually, they were both sanctioned by BMW.

So, a pre-1983 car being presented as an Alpina usually falls into one of three categories: a car that has some random Alpina parts installed on it by God-knows-who (that isn’t really an Alpina), a car built by an authorized Alpina dealer/distributor (which may be an Alpina, depending on your definition), and a car build by Alpina themselves.

A little Alpina background probably helps. They began tuning BMWs in 1962, first by strapping a pair of Weber carburetors on the M10 in a 1500 sedan. In the 60s, they developed motors with Webers, increased-compression pistons, longer-duration camshafts (notably the BMW Motorsport 300* camshaft), and porting, polishing, and combustion chamber machine work on the head. While this unleashed lots of locked-in horsepower, it wasn’t all that innovative. Indeed, it was fairly common work that many talented machinists could accomplish. What made Alpina so special was they were the first to do it regularly and their work was pretty damn good. Then they designed some pretty neat (and very expensive) parts of their own, like the A4 four-throttle injection system for the 2002tii (they also put the A4 engine in the early e21 3-series cars).

Alpina then took a a page out of Carrol Shelby’s book and put in bigger motors. The e21-based B6 2.8 is a perfect example: They took the M30 motor out of the 5-series and plopped it in a the small 3-series two-door sedan; the earlier ones had unique fuel injection, but about half-way through the run, they changed it to stock BMW L-Jet Bosch fuel injection. Alpina, essentially, followed Shelby’s model (bigger motor in smaller car) but used motors from the original manufacturer (BMW). Their other trick was turbocharging the bigger cars that already had the bigger motors, like the 5- and 6-series (the B7).

At first, this work was done in the Alpina factory, but soon authorized dealers popped up in England, Holland, and the United States. Here, we had Miller/Norburn in North Carolina, Hardy & Beck in Berkeley California, and Dietel Enterprises in Mission Viejo, California. These authorized dealers did several things: sold Alpina parts, installed Alpina parts and built Alpina cars, and in some cases imported cars built by Alpina.

What makes it difficult to know whether a pre-1983 car is “really” an Alpina? Alpina has limited records of the cars they built – for instance, all they could tell me about my C1 2.3 is that it had been brought to them in February of 1982, not what they did to it – or anything else. And from what I’ve heard Alpina has no records whatsoever of the cars built by their authorized dealers. While a car built by Dietel Enterprises might legitimately considered an Alpina, without a record, it is simple a nice car with nice parts and maybe an Alpina dash plaque (which any yahoo could buy off eBay and put on the car).

And many folks did just that – put a bunch of Alpina parts on a car and claimed it to be the real thing. Often, there are few ways to verify authenticity and accepting a car as a “real” Alpina is an act of faith, The guy I bought this C1 from did just that; he was sure it was the real-deal, but he had no solid proof. Having built my 2002 touring with more genuine Alpina parts than many cars that left the Buchloe factory, I am skeptical of any car without documentation is a “real” Alpina.

by alpinac1_pn9him | Nov 24, 2025 | Uncategorized

October 8, 2017

Although the car was authenticated by Alpina, I assumed the worst – that the engine was not an actual Alpina lump. Yeah, the shell was touched by the Hands of God, but the previous owner who piped-up on BaT said an unethical mechanic pilfered many of the precious parts. I feared the motor suffered that fate.

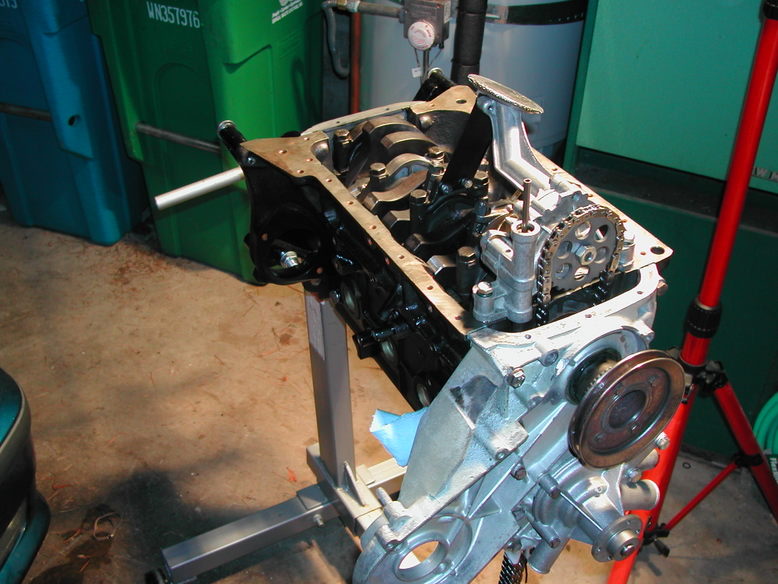

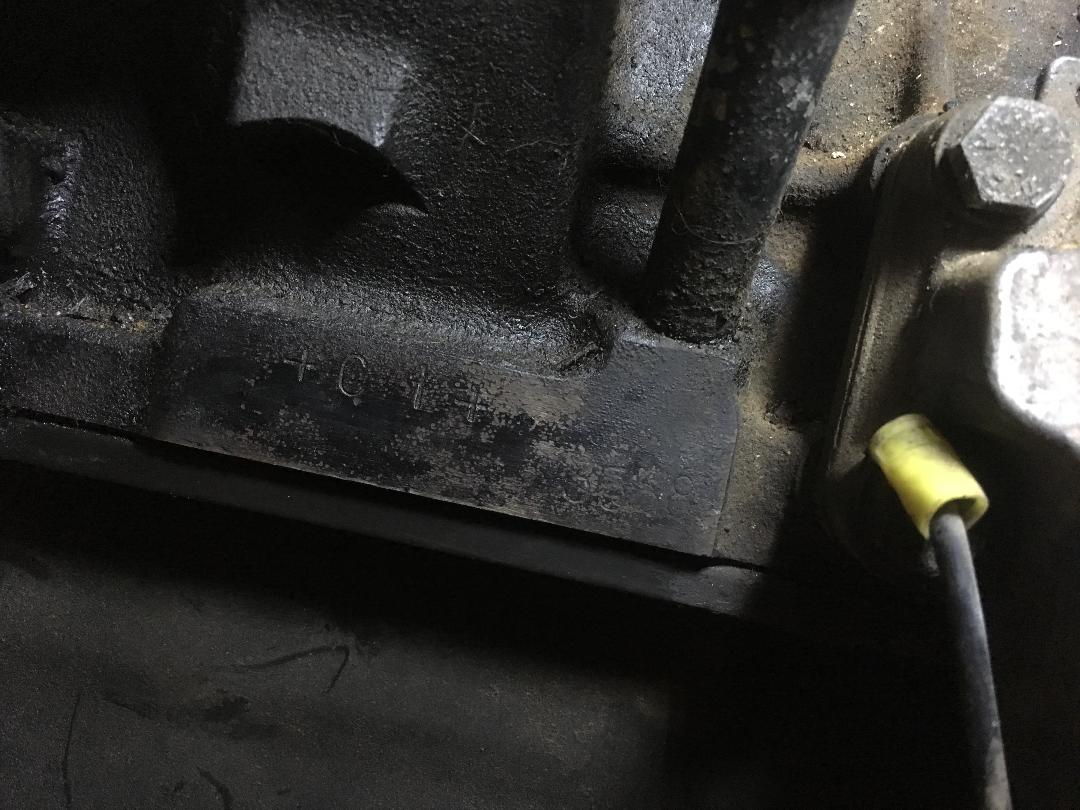

When the car was finally in my hands, I looked for the four-digit hand-stamped numbers in the block and head. I found nothing, not knowing where to look. My fear of the worst grew, but I knew I’d be able to really inspect it once I pulled it out of the body, and I’d figure it out from the serial number on the block.

Every project – at least every project I’ve done – has a pace, a rhythm; it’s own timing. But taking the engine out stalled. Removing a 2002 motor is easy, especially on a carbureted car. A 323i is a bit more complicated and, frankly, I was intimidated as I couldn’t find an English-language manual. The physically bigger motor, the unfamiliar Bosch K-Jet fuel injection, the lack of instruction on how to go about removing it, and my old-man status making me reluctant to lie on the garage floor under a car – it all added up to a lot of inertia. Motivation was also lacking because I couldn’t decide what I wanted to do with the motor: rebuild it stock or take advantage of advances made since Alpina built it in 1982.

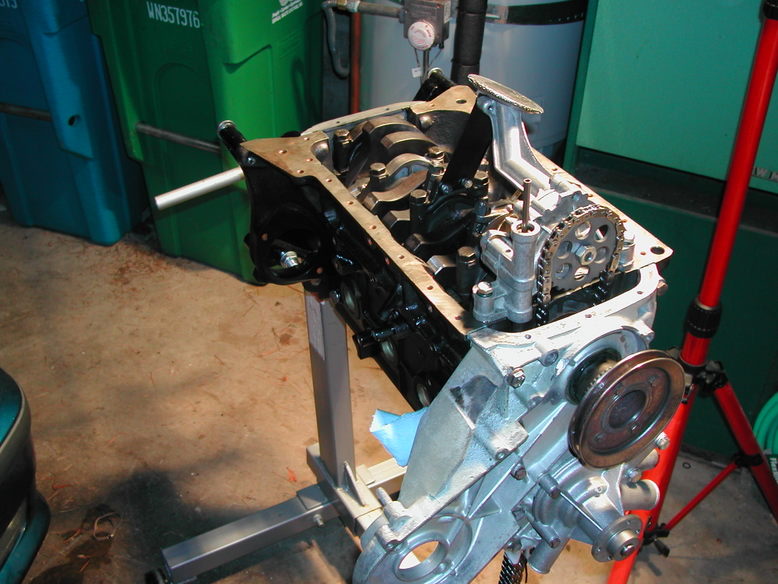

After months of hoping the motor will remove itself, I decided I had to actually get going. Late nights in the garage, disconnecting this or that, finally gave way to actually hooking up the cherry-picker and pulling the motor out. My 16-year-old son helped, much as he did with the Inka 2002 touring, almost ten years earlier.

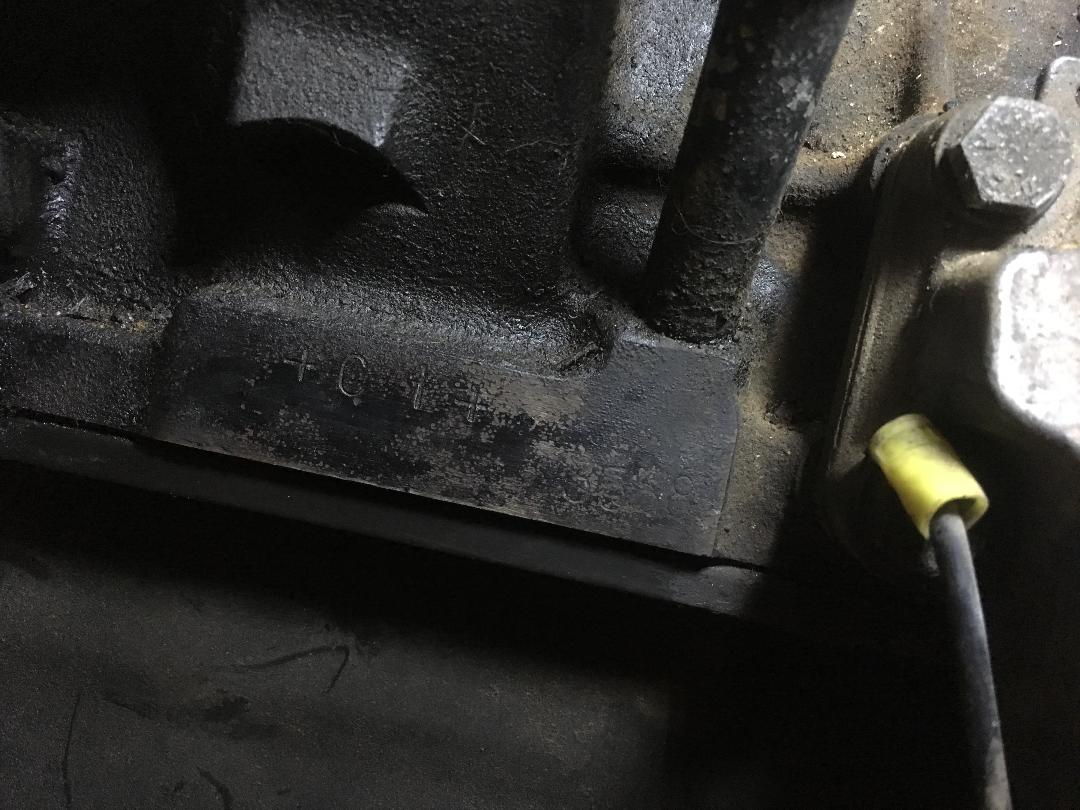

Once the lump was out of the car, I looked all over the block for a serial number – Alpina or otherwise. But I couldn’t find one. Then I asked my friend google where to look, and came upon some stamping below the distributor housing area: “+ C1 +” with a barely legible hand stamped four-digit serial number under it (3568). No one had to tell me this was not a BMW number; I knew who stamped + C1 + on a block and who used those four-digit numbers. The dance around the car, screaming “yes” and “it’s a real Alpina motor, touched by the Hands of God” was so much fun I forgot to check the head. When I finally did, I couldn’t find any numbers, but admittedly had no idea where to look (google wasn’t much help for that).

After a week of wondering if I had a genuine Alpina block but not head, a very helpful fellow C1 owner sent me a picture of the stamping on both head and block (thanks Don!) and I found the Alpina serial number on the head. Confirmed, both head and block are original from Alpina.

So, I have a motor, touched by the Hands of God, sitting in my garage, probably with a blown head gasket. What to do with that? I don’t want to modify the Alpina block or head, so do I undertake a “stock” Alpina rebuild it and put it back? Store it and build a new block into something bigger, better, and more powerful? Decisions, decisions.

by alpinac1_pn9him | Nov 24, 2025 | Uncategorized

October 18, 2017

So, I have an authentic Alpina engine, complete with the stamped-in numbers on both head and block. That engine probably has a blown head gasket and maybe a cracked head or some cylinder and piston damage. Of course, I won’t know for sure the extent of any damage until I open it up, but all signs point to the head gasket, as the car was running decently, didn’t smoke, and from what I’ve been told didn’t have oil consumption issues. I could have left the motor in situ and fixed the head gasket, if that turned out to be the problem. But there was a slippery slope to go down and you know I couldn’t resist it: I had to pull the engine; after all the engine compartment was a mess, I wanted to bring the battery back into the engine compartment (it had been moved to the trunk somewhere between Germany and my tutelage). True, it’s not necessary to pull the engine to do those things, but having it out of there made it easier. Plus, the motor needed work and that’s easier out of the body. And the shell can be repainted while the engine compartment is being cleaned-up. Oh, that slippery slope.

Then there’s the biggest reason I couldn’t just leave well-enough alone: Me being me, I want to rebuilt the engine even if it’s just the head gasket – but the real question was to what spec?

Not a big duh, but the whole point of owning an authentic Alpina is to own, well, an authentic Alpina. So, my plan was to rebuild the Alpina motor to stock specs with as many parts that Alpina used. I mean, a resto-mod of a genuine Alpina is kinda pointless.

Or is it? What if I could build a motor that looks like the Alpina motor that has considerably more power and squirrel the real Alpina motor away for the day that having it stock mattered (whenever that day was). Isn’t this the best of both worlds? The car looks stock, runs a lot stronger and if you ever feel the need to go back to stock, you have the actual Alpina motor. And aren’t I a resto-modder? Haven’t I spent my entire adult life restoring BMWs and improving on their performance?

With that goal in mind, I tried to figure out what you can squeeze more power – torque, specifically, out a motor while retaining the stock Alpina look. It seems Alpina used the stock 323i K-Jet, so first I wondered what I could out of that injection system? K-Jet is a weird system, bridging the gap between purely mechanical fuel injection like came on a 2002tii (and an early 911s) and Motronics, the fully electronic, simple to modify fuel injection. The stock 323i put out 140bhp with the K-Jet and the C1 2.3 got that up to 180bhp with some machine work and a little more cam and compression. (Alpina substituted the stock 264 cam in a 323i with a 268 cam. Stock compression of 9.5:1 was increased to 10.0:1. Both of these seemed somewhat tepid to increases to me.) So Alpina was able to add an addition 40bhp while using an antiquated and somewhat inflexible fuel injection system. To get much more power you ran into the challenge of delivering enough air and fuel through the stock K-Jet.

Trying to figure out if I could reach my goal using the stock injection, I posted on a few boards and got some encouraging responses, but few specifics. Given the vague responses, I was suspect of the claims to have developed 200bhp with stock K-Jet (that was, after all, almost a 50% increase over factory without changing the injection), especially since some were saying things like “I run nitrous and get ….” Or “with a water injection….” I mean, I was trying to have it look stock and neither nitrous or water injection are stock. I figured this was the challenge I faced trying to work within the limits of the K-Jet and it being a gray-market 323i in the USA – the rarity of the car made it so there were few who developed motors with inferior injection too far past stock. I spoke to a friend who owns a shop and he suggested I build it stock because getting enough air through the stock parts was going to limit whatever I did. He made the very valid point that “you already have a really fast Porsche and you’re not going to be able to build this to perform better – and that’s not the point of the car. Being an Alpina is. Leave well-enough alone and enjoy it for what it is.” Of course, he was right.

But then I got an email from another C1 2.3 owner who saw one of my posts asking about building a performance motor with stock parts. He built a 2.8 liter motor but not with stock parts – but they were stock looking. He took a M20B25 block (from an e30 325i) and head and Porsche K-Jet parts that would flow the necessary air and fuel for the bigger motor and put his stock motor aside to save it for the day that having it stock mattered (whenever that day was). A couple of emails back-and-forth and I had enough specifics to make my decision and dive in to the next step of the project, building the motor. After all, if he did it, what could possibly go wrong with me trying to do the same? Well, we’re about to find out!

by alpinac1_pn9him | Aug 4, 2025 | Uncategorized

August 4, 2025

From the title of this post you might think the Alpina has run into a problem. If you did, you’d be wrong. The Alpina, finally, is on a truck coming to its new East coast home, with all sorts of work completed. And, of course, you’ll get to read all about that soon enough. But today, rather than chronicling or exploring the restoration of the Alpina, I’m getting all introspective, exploring my car problem.

There have been many constants in my car obsession but it has also morphed over the years. Of course, two of the main constants have always been financial and garage space constraints. Over the years, both of those remained but have eased a bit. My wife and I are serial renovators and as we’ve moved, we’ve both made some money on the houses and been able to be more picky about the amenities. One of those amenities was the garage and one-car garages became two-car and now that we’ve moved to the East Coast, we have the luxury of a three-car garage. Not huge space, but better.

The biggest constant has been the type of car I desire. While I’ve lusted after Ferraris (my son’s middle name is Dino!) and Porsches (and was even lucky enough to have a few over the years), as far back as high school and college (circa late 70s and early 80s) I’ve focused primarily on sport sedans. My first two cars were a1972 Ford Carpi and a 1969 Triumph GT6+ but I always had my eye on a 1969 BMW 2002. Was it the infamous David E. Davis article in Car and Driver? Was it my high school friend Tedd who waxed poetic about his 1600? Was it that every article I read about a boxy sedan—be it a Datsun 510, Mazda RX2, Opel whatever—that were all compared to pinnacle: the 2002? Who knows. But I lusted after one.

I finally got enough money for a 2002 by working for a year before college. Even though I could afford to buy one finally, I couldn’t afford to pay someone fix it. So, I taught myself how to work on the cars. Mostly I learned from the Chilton manual and articles and tech columns in the BMW Car Club magazine The Roundel. Mike Self, Mike Miller, Rob Siegle, they gave me the confidence to try it.

The combination of financial necessity and unwarranted confidence led me to plenty of mistakes along the way: I have fond memories of replacing the rear brakes on the 2002 using the BMW issued scissor jack in the Star Market dirt parking lot behind my apartment building while I was in college in Boston. The car only fell over once; don’t recall how I got it back up on the jack to finish the job but I know I did.

The early years were primarily focused on just keeping the car running but I always wanted to tinker, to improve. A Momo steering wheel, BBS wheels, a Weber carb. Then after law school I built a 2002tii I bought in pieces. It had a full suspension (Bilsteins, ST springs, Alpina sway bars) and a hot motor (292 cam and Alpina valve-train). For about 10 years I tried to thread the street/track needle: I’d daily drive the car but on the weekends it was my autocross or track weapon. Trying to serve two masters seemed to fully satisfy neither; most notably the suspension was barely acceptable for the track yet grueling on my daily commute. And, while I loved driving the cars fast in a controlled environment, I didn’t love it enough to dedicate the time to get as good as I wanted. Put differently, other priorities—career, wife, kids, enjoying life—interfered with the track/autocross hobby.

So, my car obsession became less track and more street focused. While I still tinkered, the modifications were less extreme and focused on making it better than BMW’s compromises for the masses and the marketing department. Wheels, lowered suspension—but not too low or aggressive, after all this was my daily driver and I took the kids to school every morning. A steering wheel. Sport seats. Maybe even a short-shift kit.

I had some fun daily-drivers, too. A 323i e21 Baur with a 325i, motronic M20 swap; a e28 535is; and after my wife hit a stock purchase out of the park (I swear there was no insider information!), I got a e34 540i M-Sport. I called it my 4-door 911 (once I owned a 911 I realized how silly that was, but that’s another Oprah show).

By this point, I had three primary car-nut lives: the kid who could barely afford what he wanted; the young man who built his street/track dual use car; and the adult who couldn’t stop tinkering. They all had commonalities, constants that hid the differences between them. The commonalities were tinker, tinker, tinker; improve over stock, rise and repeat.

During the last phase I could afford to have a daily-driver and restore something on the side. First, I got a 1972 Inka 2000 touring that I built with all the Alpina parts I had been squireling away for a decade or two. Took a couple years to build and it was a great little car but after a while I wanted another project, so I sold it. The road eventually led to the e21 Alpina, my longest and more comprehensive project.

But has Father Time caught up with me? I’ve reached an age where this might be my last project. I’m on the wrong side of 60 now, just had my second joint replaced, two heart “procedures” in the past ten years, and a cancer diagnosis (thankfully benign). Even more importantly, when I wrench on the cars, I often feel more frustration than the zen-like joy it used to bring. And my back aches for hours after. I still want to put a lift in my big (for me) three-car garage but is it worth it now?

And the age shows in my daily-driver. It’s still a BMW, a Sunset Orange f31 330i wagon. The car is a testament to the compromises of old age and practicality: an automatic, all-wheel drive for winter driving, turbo four for gas mileage. Yes, it has factory sport seats and I added a custom thicker steering wheel and (knock off) M3 CSL wheels. But, after buying all the parts to lower the suspension, I ended up selling them and leaving it stock—something I’ve never done before. Why? The road around here are rough, I like having my wife in the car with me and she hated the last f31’s lowered suspension, and honestly, for the intended use of the car, stock suspension is fine. It’s funny: my first 2002 got a steering wheel and wider wheels, the two things I’ve done on the wagon. Fifty-something years ago it was because that was all I could afford. Now, it’s because it’s all I want. I’m not sure how I feel about this, but it is full circle.

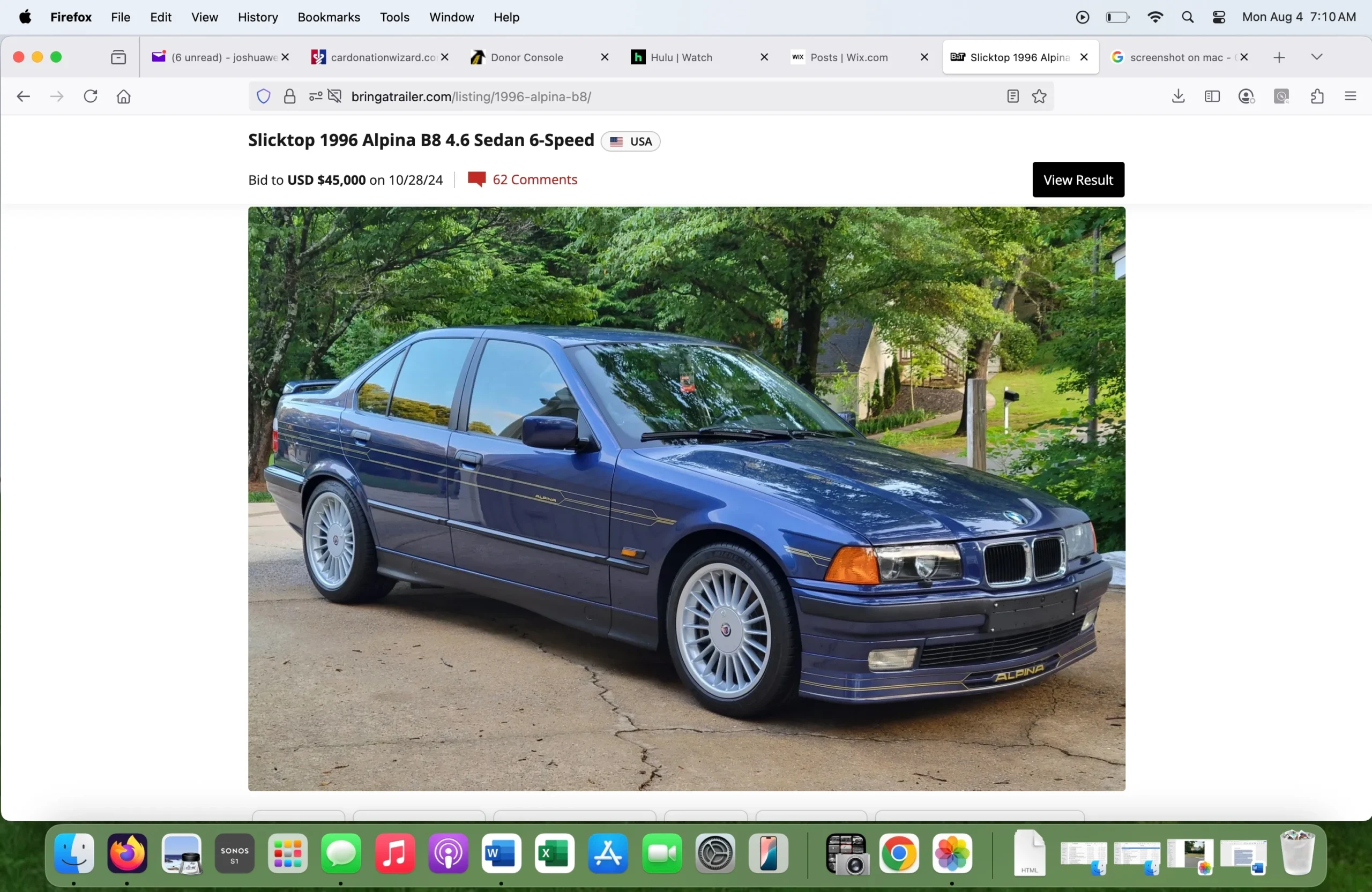

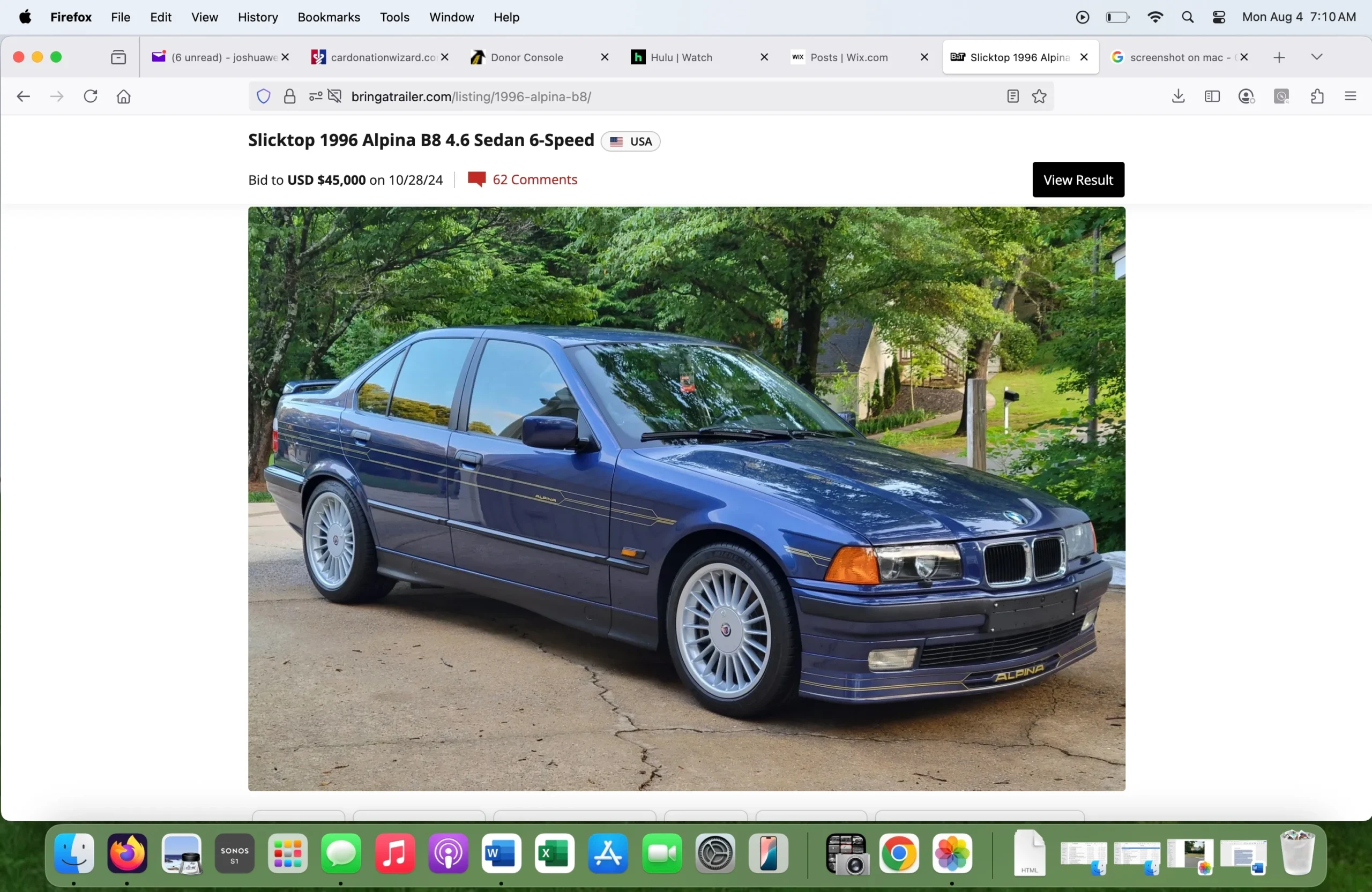

Does this progression, this arc affect the Alpina? Maybe, maybe not. Like most carboys, I have a wandering eye and mind. And the daily emails from Bring-a-Trailer and Cars and Bid only make it worse. Do I want to sell my 1972 2000 touring and the Alpina and get something that fits my old age better—i.e., something that requires less work and is a little less vintage/a bit more comfortable? Would I like a e46 M3? An Alpina B8 4.6 e36? Something a bit more “plug and play” than a 50-year-old restoration project? I was the high bidder on this auction and wonder if that would satisfy my elderly car obsession.

After the auction did not meet reserve, the buyer and I negotiated for a bit before someone else stepped up. I regret not getting it but I also know I’m torn: I like vintage cars and an e36 isn’t vintage to me. Can I find something that threads that needle, vintage but more comfortable and reliable? Am I in the adult version of that street/track phase where I’m trying to serve two masters but satisfying neither? Can this carboy ever be happy? All I know for sure is that I just keep obsessing over cars that could be my next toy or my next project. And then I wonder when is this going to stop? When will I be satisfied? If history is any guide, never. But in the meantime I’m just going keep asking when is this gonna stop?

by alpinac1_pn9him | Aug 21, 2024 | Uncategorized

August, 2024

I try, sometimes successfully, to have a theme for every post here. The last post, When good enough isn’t good enough, was about re-repairing things in anticipation of Legends of the Autobahn 2024 and also bringing the restoration up to a new standard. In doing so, it seems, I got a bit ahead of my skis.

Getting ahead of my skis is something I try not to do. And usually it’s easy to accomplish: just don’t write about anything until it’s finished, after I know the full arc of the story. But I violated that rule last month when I wrote, among other things, about the fix to the flickering oil pressure gauge and having the body shop replace the transmission speedo gear so I’d have a functioning speedometer and fixing the previously addressed rust in the frame-rail. None of those worked out as planned and the story arc changed things in big and small ways.

Even though I had dropped the Alpina off at the body shop well in advance of LoTA they didn’t have time to fix the frame-rail. And that was disappointing but understandable: they had at least one other car in there being prepped for LoTA and several, you know, getting repaired. Conversely, the frame-rail was an optional project, not nearly as mission critical as other things on their plate, like trying to get another very nice e21 323i together for Monterey.

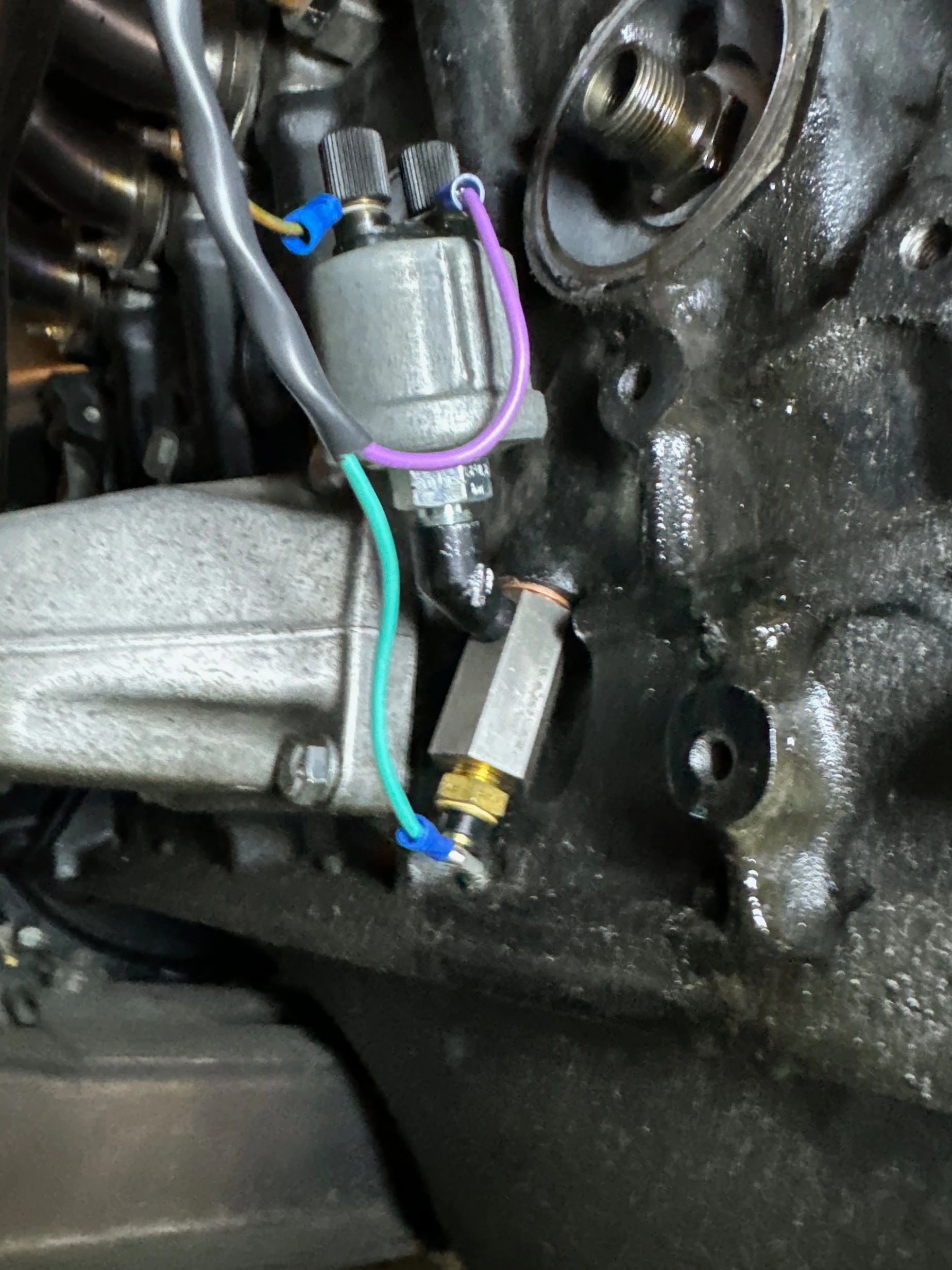

Although this is not the body shop’s fault, the first thing I noticed upon driving it home was that the speedo gear change did not fix the non-functioning speedometer. I spent the drive strategizing how to fix that and the stumbling on acceleration. Before this revelation I planned to ship the car to my new home in New York and, over the winter, becoming proficient enough in K-Jet fuel injection to fix the stumbling/lean running myself. I unsuccessfully tried this in the 1990s when I owned my first e21 323i but was determined to do better this time. The transmission, however, added a new wrinkle. So, I hatched a new plan to take the car to Sacramento and have Stu, who worked on the transmission before it was put in, fix the speedo drive. And he also happens to be the best person I knew for fine tuning the K-Jet. To make things even better, another friend drilled and tapped a spare fuel pressure regulator to make it adjustable. A phone call to Stu and a plan was made.

Once I got the car home, my first mission was to change the oil pressure sender. You may recall, I figured out that I had put in a 80 PSI sender in the car but was using a 150 PSI gauge. I put the new 150 PSI gauge in but noticed, when taking the old one out, that it was not an 80 PSI sender, but the same as the new one I was installing. To add insult to injury, once the oil was warm, the idiot light still flickered. Also, the pressure never gets above 60 PSI when cold or 45 when warm. All this isn’t dangerous—more just annoying and perplexing, as ever M10 I’ve built hovers around 60 PSI when warm and 90 when cold. I’ll get to the bottom of this but will wait to explain the fix (or should I say anticipated fix) because I don’t want to again get too far over my skis.

Other than the lack of speedo and flickering oil pressure light, the drive to and from Legends was uneventful and the show was a lot of fun. I spent most my time talking to folks. I knew several of the participants, some who were pretty good friends, and walked around socializing most of the day. I saw Julius who owns a e21 B6 (but not running well enough to bring to Legends), Ricardo who is restoring and modifying his e21 (and got to meet his son who is going to my alma mater), Rob who owns several 2002s but was having his 2002tii with many Alpina bits (including an A4 injection system) judged in the concourse, and many 2002 friends (Jan, Bart, Delia, etc.) and some new friends. And, of course, the Alpina crowd, too. Because of all the socializing I didn’t really have a chance to take many—ok, any—pictures but I was able to harvest a few cool ones from the BMWCCA Golden Gate chapter FaceBook page and other such places. It was a bitter-sweet Legends for me, given that I’m moving away: It was great to see so many folks I know, some well and others car acquaintances. But I worried about how long it would take to make the same sort of connections on the east coast. Of course, I could always avoid the August humidity of the east coast and make Legends an annual trip to California….

After a day of rest, I got up early Saturday morning to take the Alpina up to Sacramento. By the time I got to San Francisco, where I stopped to fill the car up with gas, it was drizzling. Apparently, the tires didn’t like that as I accelerated up the cloverleaf back onto the highway and the rear end came around. In the spin, the car jumped a curb. After the visual inspection everything seemed fine and I was back on my way. A few miles later, however, some unusual noise was coming from the front and steering required more effort. I got off the highway and confirmed my suspicions: a flat tire. Luckly, I recently got a used wheel with decent looked rubber. I called AAA; there was a truck minutes away, the spare was installed, and I was back on my way!

At least for a while. About 50 miles later some weird thumps could be heard. I wondered if it was the pavement and changed lanes. It would go away for a bit but came back. And got worse. Soon it was bad enough that I pulled over and saw that the spare was disintegrating.

Apparently, the good rubber was really old and rotten. With no usable spare, I called AAA; almost 90 minutes later, the truck showed up and towed me to the shop. Stu then took me to the train, which I took home. I wasn’t happy about how the trip turned out but I was thankful that I didn’t have a blow out with the disintegrating spare and that the spin didn’t appear to cause any more damage than a flat tire.

So, the car is in Sacramento, back in Stu’s hands. When I get it shipped east I’m hopeful that the speedo will work and the fuel injection is dialed-in. And I’ll work on the that flickering oil pressure light. But I won’t get out over my skis and declare any of these things fixed!

by alpinac1_pn9him | Jul 22, 2024 | Uncategorized

For a change, a fair amount has happened since the last post about making it to Monterey last August for the Alpina corral at Legends of the Autobahn. Sure, nothing as monumental as getting it running after being dormant for seven years, or ensuring she was roadworthy, or taking a couple hundred miles trip without incident. But even if the work didn’t mean big steps forward, the many little things, and a few medium-sized ones, did add up to some fulfilling progress.

And that fulfilling progress begat a new dynamic: redoing several things that were good enough to make the car roadworthy but now aren’t good enough given how nice the car has turned out.

The little things were, well, little, but also made the car more enjoyable or presentable. First was to affixing the Alpina emblem and the model designation on the back of the trunk lid. A little measuring, blue painter’s tape and the emblems were on. They look good, although I suspect the C1 2.3 emblem is for an e30 and larger than the e21 version. But you get what you get and this was the only one I could find.

They dialed in the fuel injection and attached the heater controls so it actually has some climate control. And they chased down some wiring gremlins. They even got the speedo working. For a day or so. Then the transmission speedo gear crapped out again. Oh well! Not sure if the replacement was also compromised–it was a used piece as it’s NLA form BMW–or if there is an issue inside the transmission.

I’ve also been slowly getting the auxiliary gauges installed. I was going to use all VDO gauges for oil pressure, temp and voltage. But I decided to have the two oil measurements and an air-fuel ratio gauge instead of my usual voltage. The air-fuel ratio gauge doesn’t match the VDO gauges but it’s provides some important information—at least for now, while making sure the fuel injection is all dialed it. I may later switch in the voltmeter if the air-fuel ratio gauge proves less useful in the long run.

Later, I braved the heavy rain to take it to the Bay Area 2002 Swap and Show, but the rain was so bad the show was canceled shortly after I arrived.

The good enough but not good enough was an interesting development. My mission since the pandemic started was to get the car out of the shop in Sacramento and running. That was accomplished, with much labor and many posts here, about a year ago. Since then, I’ve had time to digest what this car is and what it isn’t.

I’ve restored a bunch of vintage BMWs, mostly 2002s but also did a lot of improving on my e12 B7 Alpina. But none of them were that nice, which was fine with me; I like drivers, not show cars. And this car with it’s 2.8 liter engine and close ratio 5-speed is certainly a driver. But the paint is pretty nice. Not great, but a solid nice! Yes, there are flaws, but it’s shiny and looks great with the Alpina stripes. As e21s go, it’s a very solid build. It’s a nice car, a step or two above the usual drivers that I build. The getting-it-running-and-let’s-see-what-we-have approach that I had over the past several years has begat something a bit better than what I’m used to creating and, frankly, I was at a crossroads with the car: it was either time to pass it along to someone who would pay me a bunch of money for a rare and nice car or acknowledge that a sane person would never sell it but would instead drive the piss out of it and fix some of the hangnails. I took the latter route.

The beauty of this car is that the paint has enough flaws that it shouldn’t be squirreled away from the world in a climate-controlled garage but is nice and shiny enough that, well, it draws a lot of attention—and, most importantly, not so nice that I’m afraid to drive it and get another paint chip or two. With that in mind, there was work I did before that was good enough—good enough to get it running and evaluated—but wasn’t good enough for what it is I discovered after that evaluation.

So, what did I redo? I had the headliner replaced by The Resto Shop; the original installation had flaws—the cuts for the corners were too deep and showed, plus none of the interior hardware, like grab bars and interior lights, were cut out. Finding the right place to cut for them without making mistakes was a fool’s errand so it was live with those inevitable flaws or redo the headliner; I choose the latter and they did it right and now all the interior hardware is in. (They did a bunch of other little things, too.)

The old headliner–you know, the one that was 3 years old–was clean but didn’t look so good. And I had no confidence that I’d be able to find where to cut for the grab bar screws or such.

The next act of re-plowing fields was done by North Bay Bavarian; they install a new exhaust and headers. The car had a decent set of headers and an Anza or Supersprint exhaust that looked very aftermarket. Neither had large enough tubes to flow the exhaust from the larger engine. I found Supersprint made a copy of the Hartge 323i RS exhaust and headers, which is a high-flow system and, short of a genuine Alpina exhaust (which I couldn’t find), this was the next best thing. They look and sound great and seemingly flow more than enough exhaust.

Also making the drive more pleasant will be a couple of frivolities I spent the last few weeks getting done: I installed a stereo and speakers and even replaced the ugly faded carpet on the rear hat shelf with some nice black vinyl.

It’s about a month until Legends of the Autobahn 2024 and, of course, I’m planning on going. Partly because it will be my last, most likely (we’re moving to the east coast and the car will be too far away from Monterey). But mainly to join the Alpina Corral again. This time the car should be even more fun to drive there but it still won’t have air conditioning—a luxury I keep vacillating on whether to (re)install…..

Then I drove the car up to Santa Rosa and dropped it off at North Bay Bavarian. The did a bunch of stuff that was above my paygrade. They put in an adjustable suspension, both front and rear, to get rid of some the excessive camber and caster.

Then I drove the car up to Santa Rosa and dropped it off at North Bay Bavarian. The did a bunch of stuff that was above my paygrade. They put in an adjustable suspension, both front and rear, to get rid of some the excessive camber and caster.

Once installed the oil pressure gauge was vexing me. The idiot light would flicker on idle and the pressure seemed low, around 30-40 PSI. After a bit of troubleshooting, I realized that I used an old sender I had left over from another project and that was a 0-80 PSI gauge whereas I was using a 1-150 gauge. The new sender is on order and the problem should soon be solved.

Once installed the oil pressure gauge was vexing me. The idiot light would flicker on idle and the pressure seemed low, around 30-40 PSI. After a bit of troubleshooting, I realized that I used an old sender I had left over from another project and that was a 0-80 PSI gauge whereas I was using a 1-150 gauge. The new sender is on order and the problem should soon be solved.

The last bit of redoing is in progress. The car is back at the auto body shop to correctly fix the rust that we ground out and covered up. While the prior repair was sufficient, it is ugly and there is a possibility that the rust will come back. The body shop will grind it all out and weld in new metal within the frame rail correctly. It will look factory and be fitting of what this car has morphed into.

The last bit of redoing is in progress. The car is back at the auto body shop to correctly fix the rust that we ground out and covered up. While the prior repair was sufficient, it is ugly and there is a possibility that the rust will come back. The body shop will grind it all out and weld in new metal within the frame rail correctly. It will look factory and be fitting of what this car has morphed into.

While in the body shop, the 3.22 Limited slip differential will be installed and a new (used) speedo gear in the transmission–so hopefully the speedometer will work. The new diff will lower the revs at freeway speeds and make the drive down to Monterey a bit more pleasant.

While in the body shop, the 3.22 Limited slip differential will be installed and a new (used) speedo gear in the transmission–so hopefully the speedometer will work. The new diff will lower the revs at freeway speeds and make the drive down to Monterey a bit more pleasant.