Sluething the car (how I found my Alpina)

September 1, 2017

I’m a serial renovator – you know the type, I buy run-down houses, live in it for a bit, fixing up a house I couldn’t otherwise afford. And after about five or 10 years, I sell the house and move on to the next project. What does it have to do with this Alpina? Well, I’m the same with cars.

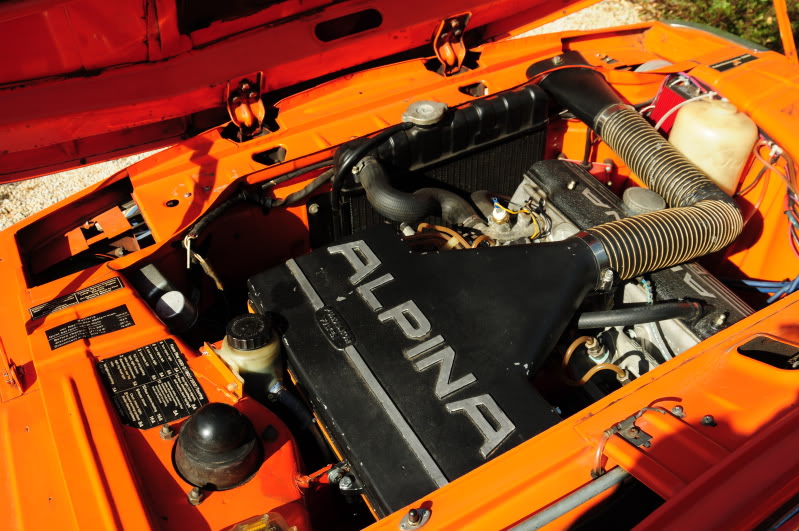

I buy old BMWs, and do a resto-mod, mostly on 2002tiis. I modify them, often with vintage Alpina parts that I had squirreled away over the years. Most recently I built an Inka 2002 touring with virtually every Alpina part available back in the day, including a complete Alpina A4 four-throttle, kugelfischer-based, mechanical fuel injection system (sporting the appropriate personalized plate FAUX A4).

While it’s fun building faux Alpinas, I’ve had a hankering for a real, honest to God Buchloe-built Alpina. For years I’ve been looking for the right car but it’s always alluded me; they either weren’t California legal or a real Alpina. The few that ticked both boxes were too expensive or too much of a project for a shade-tree mechanic like me.

One random morning, while drinking my coffee and reading an email blast from Bring-a-Trailer, I spotted a listing for one of my favorite Alpinas – an e21-based C1 2.3 (https://bringatrailer.com/listing/1982-alpina-c1-2-3/). The pictures weren’t the most revealing, but it looked decent. The interior was pretty much all there but old: disheveled, faded, and cracked. The mechanics looked overly greasy, but were claimed to be in good condition, including new brakes and suspension (with the original Alpina/Bilsteins, ready to be rebuilt). Even from the (deceiving?) pictures on BaT, the car clearly needed someone to lovingly massage it, but didn’t appear to be a basketcase. Could this be the one for me?

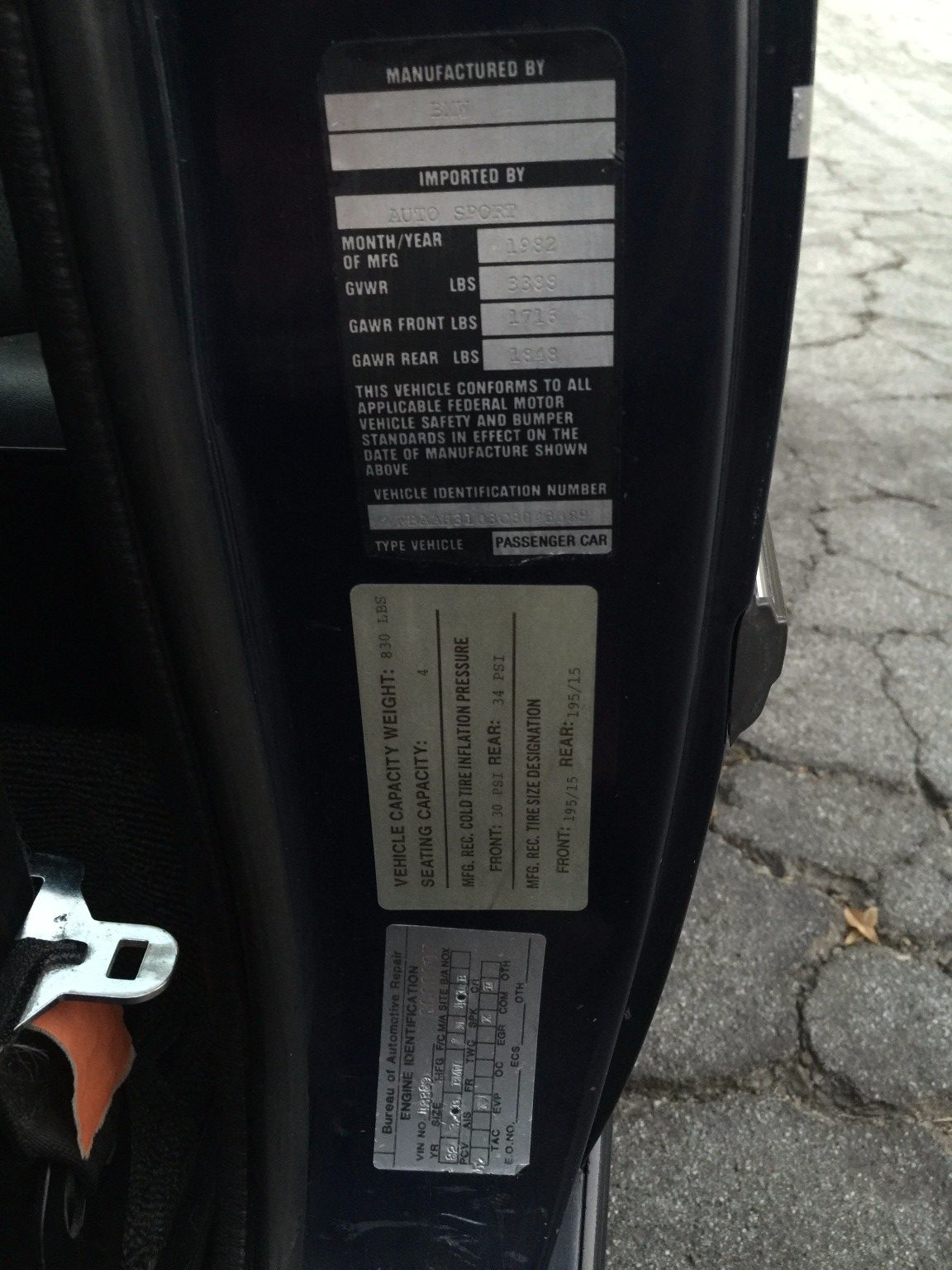

My requirements were that it was registerable in California and a genuine Alpina. Figuring out whether it was California legal was easy. To register a grey-market car (a Euro-market car not imported by BMW of North America) in California, it needs a valid so-called BAR sticker, an indication that the car has been approved by the California Bureau of Automotive Repair and complies with smog requirements at the time the sticker was issued. Cars that have a BAR sticker and have been continuously registered in California since getting the sticker are grandfathered in. If the car moved out of state after getting a sticker, it needs a new sticker if it moves back! Because getting the sticker is an expensive and difficult process, a valid BAR sticker is the holy grail for euro-car fans.

Looking at the pictures on BaT, the car had California plates, looked to be currently registered in California, and had a BAR sticker. I contacted the seller and was able to verify it had been continuously registered in the Golden State and was smog legal. One hurdle cleared!

Next, the most important – and certainly more difficult – hurdle: is it a real Alpina? That may seem like an easy question to answer, but it actually isn’t. Back in the day, it was hard to know if a car was a genuine Alpina or “just” an old BMW with some Alpina parts on it. Even an Alpina dash plaque did not guarantee authenticity – anyone can buy the plaque (available on eBay even now!) and have it properly engraved. Hell, I did that with a gray-market 1980 323i I owned a couple of decades ago. Without paperwork, like a bill of sale with the VIN, it often felt like an act of faith to believe a BMW was a real Alpina. Popular wisdom was that even Alpina did not have records from back in the 70s or 80s and that they were hostile to inquiries.

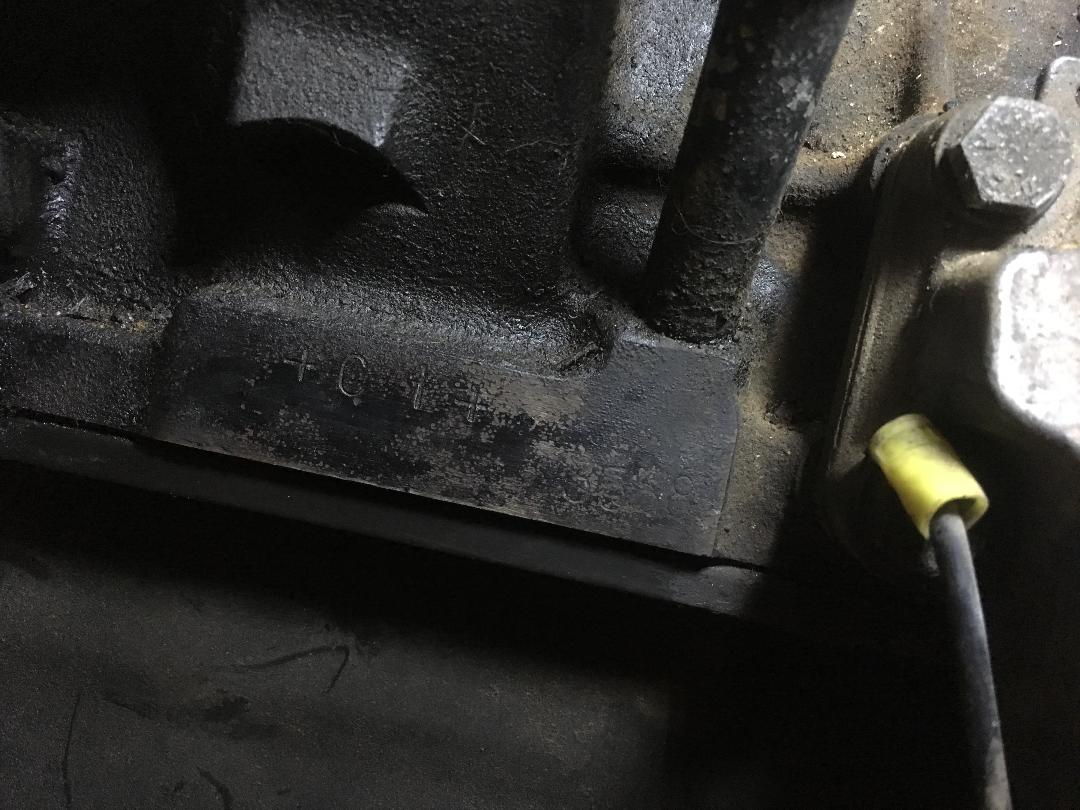

Reading the comments on the BaT listing, it was clear that several others were on the hunting for some indicia of authenticity. One guy asked the seller to check for the Alpina stamping on the head and block. When the seller didn’t things got nasty; he was accused of trying to pawn off a 323i with a bunch of cool parts as a real-deal Alpina. I chuckled at the outrage, having seen too many so-called Alpinas that couldn’t pass the originality test.

Then a previous owner piped up, claiming it was a real Alpina with an unethical mechanic pilfering many of the unique parts. He provided some interesting history, including the importer, but was largely ignored. And, to make it worse, the seller rose to the bait, engaging with those who cast doubt on the car. An early bidder wondered if he was a fool for jumping out to a $9,000 bid early-on. It seemed other bidders were scared away by the constant cacophony of callous comments, and they thanked the haters for saving them from buying such a questionable car.

One comment politely summarized the mood of the bidders: “Been watching this one with interest and the glaring omission of stamped block and head photos and/or verification from [the Alpina factory in] Buchloe of its authenticity are growing problems for the seller. … Until then I’m in the camp that it’s a 323i with cool parts and would bid accordingly.”

The auction ended with the car not meeting reserve, the highest bid being $10,000 (mine was second highest at $9,600). I bid on the car on the theory that it was worth around $9,500 (to me at least) even if it was “only” a 323i with a bunch of cool Alpina parts and an all-important valid BAR sticker. I could, after all, make another “faux Alpina,” like I did with the Inka touring. And it had a bunch of expensive parts left (ultra rare seats, some suspension components, correct wheels, shift knob and steering wheel) and an Alpina dash plaque – real or not.

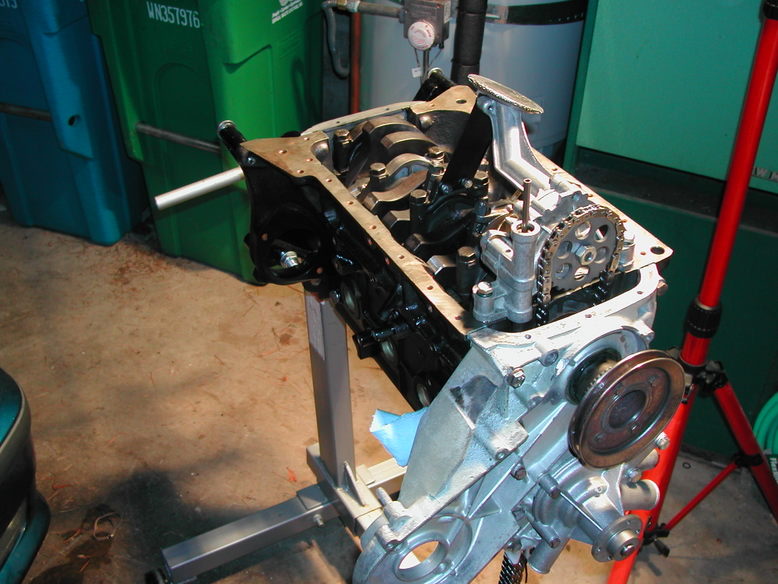

Then two things happened. The first – getting a pre-purchase inspection – almost made me walk away. A few minor and odd flaws were revealed – like the tow hook that is welded to the spare tire well was torn out and the exposed raw metal was rusting – and some other similarly quirky problems that weren’t big deals over all. But there was a big issue: a compression test that revealed low compression in two adjacent cylinders, indicating a blown head gasket – or possibly worse, like a cracked head or bad rings in adjacent cylinders. I wasn’t that worried about an engine rebuild as I’d do everything myself other than the machine work, but the project was getting pretty expensive – especially if all I was getting was a 323i with a bunch of cool Alpina parts and BAR sticker.

While arranging the PPI, I again attempted to sleuth out the car’s history. I talked with the owner, but that offered nothing new. Then I tried to chase down the guy the previous owner said imported the car, Mike Dietel. Mike used to own one of the three Alpina authorized shops in the USA (and had done some really cool home-made conversions in his shop in Orange County). Got nowhere with that. Because I either have too much time on my hands or don’t understand how to prioritize correctly, I kept scrutinizing the pictures, comments, and the seller’s answers on the BaT listing. One of the most critical comments chided the seller for not contacting Alpina to prove it was authentic. But wait, I thought. Decades of conventional wisdom said that Alpina did not have records from back then. And that you needed an “in” there to even have a conversation about cars from the 70s and 80s. Could that conventional wisdom (and my acceptance of it) be wrong? Mr. Critic implied he emailed Alpina and they authenticated a car for him. Frankly, I figured he was blowhard know-it-all, but if he was right…..

I emailed Alpina with the VIN and a day and half later I got a lovely email from Elisabeth Steck in the Automotive Sales division of Alpina: “I have checked and I found the car in February of the year 1982 and we have had it in our company for modification. Hope, this will help you.” Since the car was built in February of 1982, it seems it went directly there from BMW. Eureka! BINGO! Suddenly the car was more than reasonably priced. And, importantly, the right amount of project for me. Eventually, after a bit too much negotiation, it was mine. We arranged shipping, I drove the car to my secure, undisclosed location and have started taking it apart.

So, I now have a new project – this time a real Alpina, with a bunch of genuine Alpina parts. Requiring lots and lots of work to bring it back to its past glory, just the way I like my projects. And I should be ready to sell it in about five or ten years.