Some more progress and, SPOILER ALERT, the motor is in!

A little over a month ago there was the first progress update in two years. Because of the pandemic I had the time to go up to Sacramento regularly and get moving the project along; Stu welcomed this because he didn’t have time to do it yet wanted to see things go forward. The goal was for me to go up at least once a week, which I’ve been able to do since the last post.

Reassembly presents a strange dichotomy. It is sometimes simultaneously enthralling and frustrating. It is enthralling to reassemble a car that was touched by the hands of God, the Alpina factory, seeing what they did—both sophisticated and, occasionally, somewhat primitive.

But the challenge of finding the parts to reassemble the car is frustrating. The disassembly was haphazard and parts show up in the strangest places in the shop, others missing or found after I’ve ordered new ones. At times it seems I’m spending more time searching the internet for little bits here and there than reassembling the car. On top of that, some of the parts I collected 4 years ago turned out to be the wrong ones (and can’t be returned now) or are just missing. On top of that, there’s the steep learning curve of trying to assemble a car you didn’t take apart.

The door locks are great example. They were taken out for painting and the original gaskets were nowhere to be found—probably they deteriorated and were not reusable—and new ones needed to be ordered. New ones were sourced from a local BMW dealer, but they didn’t work—they were round without indents to follow the contours of the lock body. Although the right part number, BMW apparently has consolidated those gaskets with ones from other cars and the “right” part (according to BMW) didn’t fit my car. A search on eBay found the New Old Stock ones that would work but they were in Greece (gotta love the internet!). The vendor had great feedback and several other BMW parts for sale so I clicked buy.

Four weeks later DHL delivered the gaskets and I finally had everything needed to put in the door locks. Getting the lock cylinder into the door was a trick, at least for someone like me who has never done it before. I started with the passenger side. The cylinder seemingly did not fit into the hole in the door; after fruitlessly trying to wiggling it in, I got more and more forceful, pushing it and then finally I held it centered on the hole and hit it with the palm of my hand. It barely went in and fell out as soon as I touched it. But, progress (however slight). A small hammer and gentle taps and it was in, but not by much—maybe a quarter-inch. Hit it a little harder and it went further in. Even harder and it was halfway in. Consistent gentle taps slowly morphed into firmer hits and it was getting closer and closer; it took a mere half an hour to get it firmly planted in the door. Learning how hard I could hit it took time; the fit was so tight it needed some serious force but I didn’t want to wack it too hard and damage the door. Then it took me 15 minutes to figure out how to attach little arm on the back of the cylinder to the lock; adding to the frustration was working in a tight space with no good line-of-sight. But, I figured out what parts of the door innards to disassemble to get room and sight; once I did, it was an easy job. The passenger side took 45 minutes (most of that being the learning curve), but the second one was finished in less than ten minutes. Knowledge is a powerful tool!

Four weeks later DHL delivered the gaskets and I finally had everything needed to put in the door locks. Getting the lock cylinder into the door was a trick, at least for someone like me who has never done it before. I started with the passenger side. The cylinder seemingly did not fit into the hole in the door; after fruitlessly trying to wiggling it in, I got more and more forceful, pushing it and then finally I held it centered on the hole and hit it with the palm of my hand. It barely went in and fell out as soon as I touched it. But, progress (however slight). A small hammer and gentle taps and it was in, but not by much—maybe a quarter-inch. Hit it a little harder and it went further in. Even harder and it was halfway in. Consistent gentle taps slowly morphed into firmer hits and it was getting closer and closer; it took a mere half an hour to get it firmly planted in the door. Learning how hard I could hit it took time; the fit was so tight it needed some serious force but I didn’t want to wack it too hard and damage the door. Then it took me 15 minutes to figure out how to attach little arm on the back of the cylinder to the lock; adding to the frustration was working in a tight space with no good line-of-sight. But, I figured out what parts of the door innards to disassemble to get room and sight; once I did, it was an easy job. The passenger side took 45 minutes (most of that being the learning curve), but the second one was finished in less than ten minutes. Knowledge is a powerful tool!

Another challenge was figuring out how the bundle of wires was supposed to routed through the engine compartment. I looked at the harness, which had an ugly re-wrap in electrical tape, and it was not at all apparent how to get from the fusebox to the headlights and horns. I inquired on the FaceBook e21 group and I found someone who restored a similar C1 2.3 (really, any e21 would have been fine, but it was great to find someone who did such a great job and documented it with photos). He sent pictures of his wiring and I was in business. I re-wrapped the harness in friction tape and routed it through the engine compartment.

Another challenge was figuring out how the bundle of wires was supposed to routed through the engine compartment. I looked at the harness, which had an ugly re-wrap in electrical tape, and it was not at all apparent how to get from the fusebox to the headlights and horns. I inquired on the FaceBook e21 group and I found someone who restored a similar C1 2.3 (really, any e21 would have been fine, but it was great to find someone who did such a great job and documented it with photos). He sent pictures of his wiring and I was in business. I re-wrapped the harness in friction tape and routed it through the engine compartment.

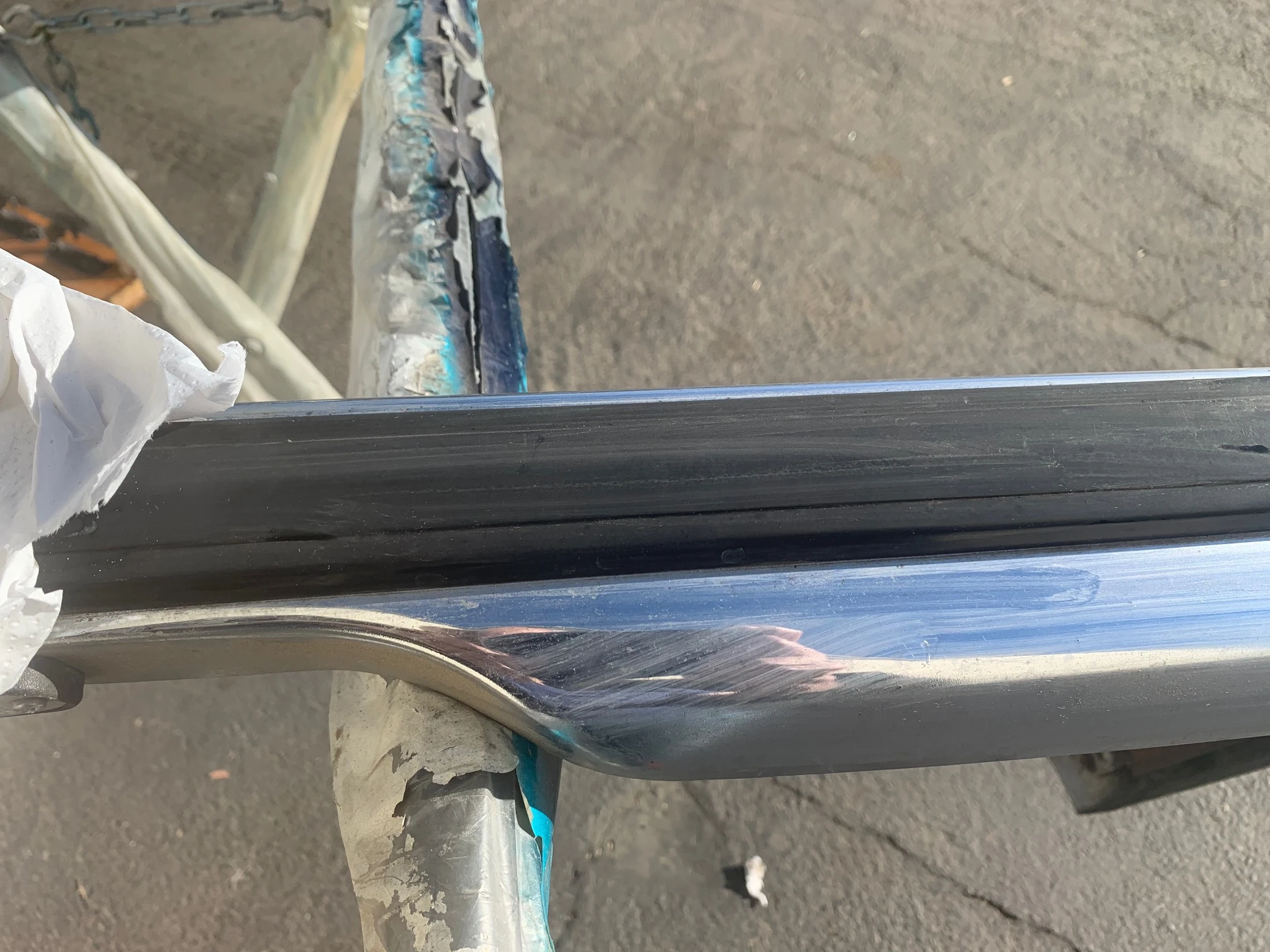

With the wiring in, next was the bumpers. They had been sitting around the shop literally collecting dust. I washed them off and then installed them.

With the wiring in, next was the bumpers. They had been sitting around the shop literally collecting dust. I washed them off and then installed them.

Then I installed the horns and lights and then grills.

Then I installed the horns and lights and then grills.

Then air dam. And talk about collecting dust! It looked like it had been painted some weird animal print pattern, but I washed it and it was good to go.

Then air dam. And talk about collecting dust! It looked like it had been painted some weird animal print pattern, but I washed it and it was good to go.

Putting the air dam on the car was one of the interesting archaeological parts of the restoration. The air dam has brake cooling ducts but behind the ducts on a stock body is the lower valance. So the boys at Buchloe cut a rectangle out of the valance to allow the air to flow to the brakes. Those cuts were uneven and kind of primitive. Honestly, they looked like something I would do in my garage!

Putting the air dam on the car was one of the interesting archaeological parts of the restoration. The air dam has brake cooling ducts but behind the ducts on a stock body is the lower valance. So the boys at Buchloe cut a rectangle out of the valance to allow the air to flow to the brakes. Those cuts were uneven and kind of primitive. Honestly, they looked like something I would do in my garage!

And sometimes it’s just fun cleaning things up and making them look spiffy; the hood latches were old and rusty, so into the media blaster they went. Quickly they were cleaned up and sprayed with lacquer. A serious improvement.

And sometimes it’s just fun cleaning things up and making them look spiffy; the hood latches were old and rusty, so into the media blaster they went. Quickly they were cleaned up and sprayed with lacquer. A serious improvement.

A project like this has a ton of small things that need to be done, like running the wire back through the small channels on the inside of the trunk lid. Fitting the wiring through those channel can be a challenge, but patience and persistence pay off.

A project like this has a ton of small things that need to be done, like running the wire back through the small channels on the inside of the trunk lid. Fitting the wiring through those channel can be a challenge, but patience and persistence pay off.

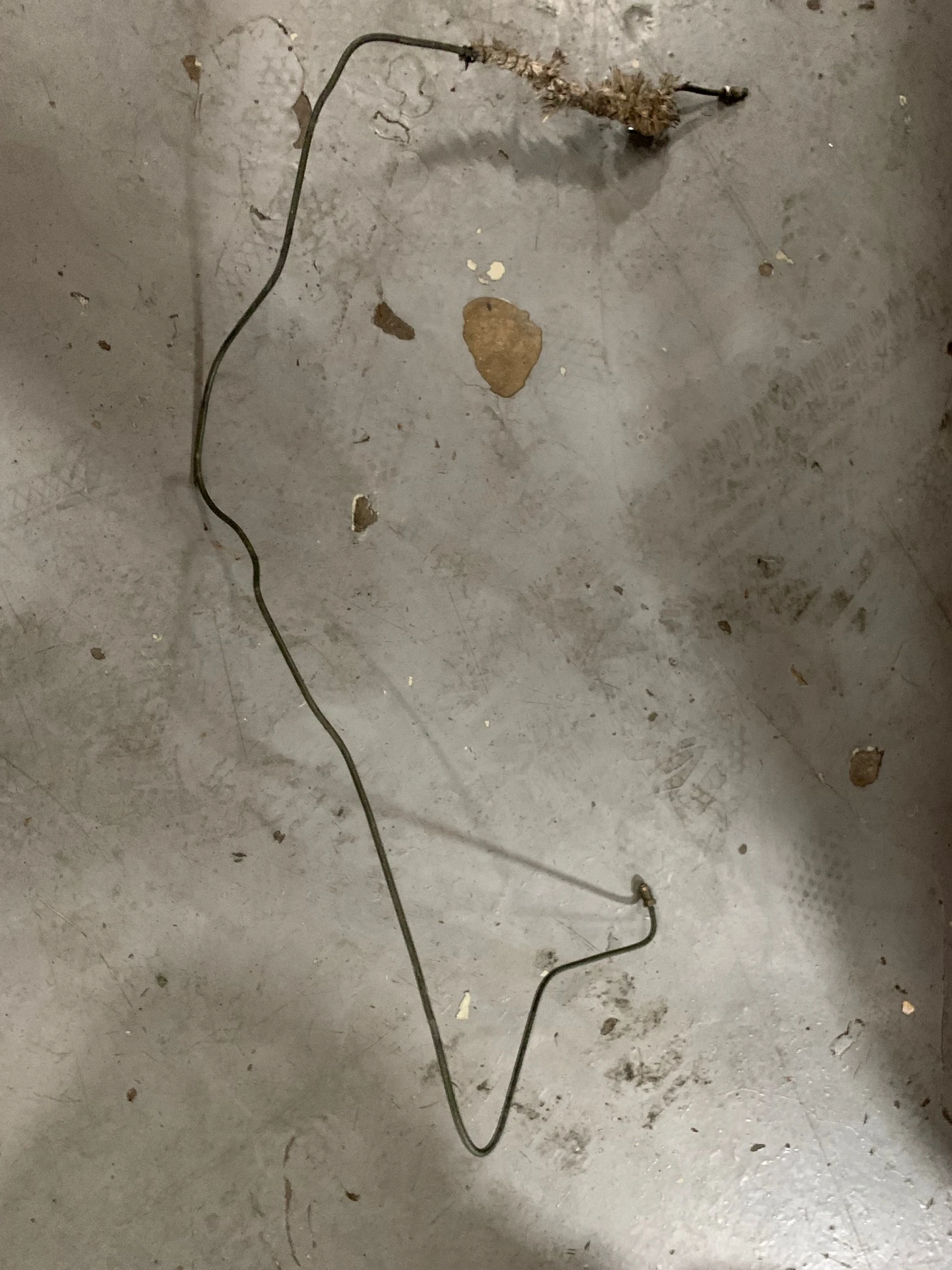

But it also has some significant challenges. One was the metal brake line to the caliper on the front passenger side. The original one was bent, weak, and just ugly.

But it also has some significant challenges. One was the metal brake line to the caliper on the front passenger side. The original one was bent, weak, and just ugly.

<PICs of old brake line>

When you buy brake line, BMW provides a straight piece of brake line that you have to bend to fit. What really makes it a challenge is that the line takes a very circuitous route from the master to the caliper and the original line was bent when it was taken out and it couldn’t be used as a template. I got a pic of the route, which was helpful but still not specific enough. We went to a junk yard and were gifted a template (the old rusted line from a carcass of a 320i). Using a template made mimicking the route much easier and the finished product looks as good as from the factory.

After that, the rest of the brake system—booster, new master cylinder, and reservoir—get installed. The brake master was one of those problems with the delayed project. Four years ago I ordered a new one but when I went to install it, the fittings where the brakes lines screwed in were in the wrong places. Too late to return it, I had to get another new one, this one fitting just right.

After that, the rest of the brake system—booster, new master cylinder, and reservoir—get installed. The brake master was one of those problems with the delayed project. Four years ago I ordered a new one but when I went to install it, the fittings where the brakes lines screwed in were in the wrong places. Too late to return it, I had to get another new one, this one fitting just right.

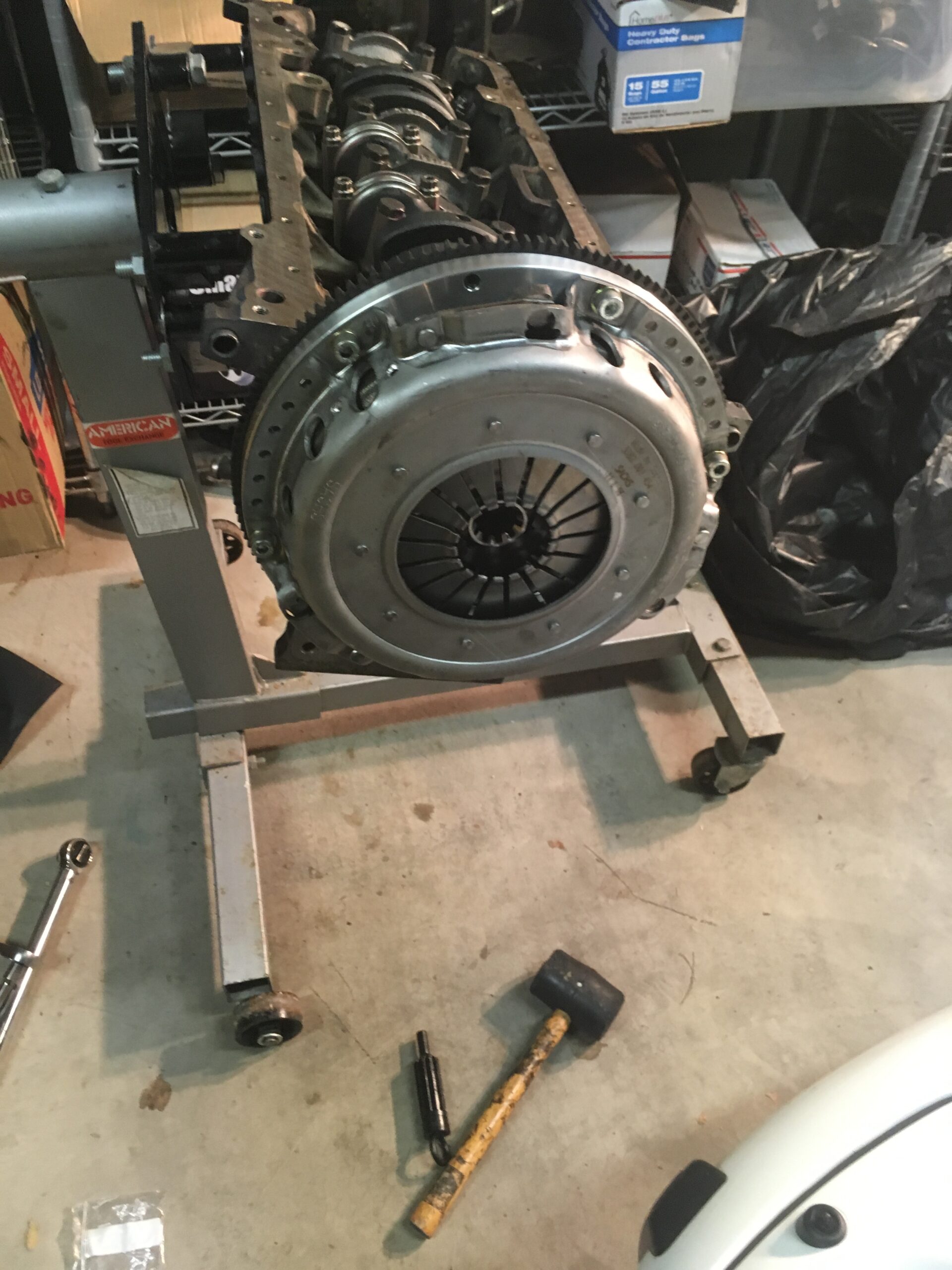

With most of the work done to the engine compartment, it was time to drop-in the motor. Putting in the motor was pretty straight-forward and two nuts later, it was part of the car again.

With most of the work done to the engine compartment, it was time to drop-in the motor. Putting in the motor was pretty straight-forward and two nuts later, it was part of the car again.

With the long block in, building it up to be a working motor was up next. The old thermostat manifold was not in great shape and need some heat to take it apart.

With the long block in, building it up to be a working motor was up next. The old thermostat manifold was not in great shape and need some heat to take it apart.

The fuel injection is up next but offers some challenges. With the bigger displacement, the stock 323i/C1 fuel injection won’t flow enough fuel. Four years ago, I bought the necessary parts (I’ll describe those in a future post) but Stu swears he doesn’t have them and I can’t find them in my parts stash. Luckily, Stu had similar ones in his parts stash and we should, soon, be good to go on that front…..

The fuel injection is up next but offers some challenges. With the bigger displacement, the stock 323i/C1 fuel injection won’t flow enough fuel. Four years ago, I bought the necessary parts (I’ll describe those in a future post) but Stu swears he doesn’t have them and I can’t find them in my parts stash. Luckily, Stu had similar ones in his parts stash and we should, soon, be good to go on that front…..

Stu worked on installing the new the headliner.

Stu worked on installing the new the headliner.

The three of us put in the windshield.

The three of us put in the windshield. And I bolted up the valance panel.

And I bolted up the valance panel. Much of my time was spent organizing the parts taken off in disassembly, which took a good amount of time. The guys at the body shop took it apart assuming they’d be putting it back together immediately so the disassembly was not organized in anticipation of a multi-year project. Finding everything more than two years later was (and continues to be) a challenge, but not an insurmountable one. While searching for unlabeled, haphazardly placed parts is not particularly fun, the project is: all my past restorations have been mechanical or interior work. Reassembling a car striped for paint is a new experience. And a good portion of the satisfaction of a project for me is the connection, the bond, one gets with a car when restoring it. And I’m feeling a special bond with his project, with its new (to me) challenges; challenges akin to building a car anew.

Much of my time was spent organizing the parts taken off in disassembly, which took a good amount of time. The guys at the body shop took it apart assuming they’d be putting it back together immediately so the disassembly was not organized in anticipation of a multi-year project. Finding everything more than two years later was (and continues to be) a challenge, but not an insurmountable one. While searching for unlabeled, haphazardly placed parts is not particularly fun, the project is: all my past restorations have been mechanical or interior work. Reassembling a car striped for paint is a new experience. And a good portion of the satisfaction of a project for me is the connection, the bond, one gets with a car when restoring it. And I’m feeling a special bond with his project, with its new (to me) challenges; challenges akin to building a car anew. Our plan is for me to keep going up to Sacramento until we get the car to a point that it can be put on the back of a trailer, driven back down to my house where I’ll finish the work.

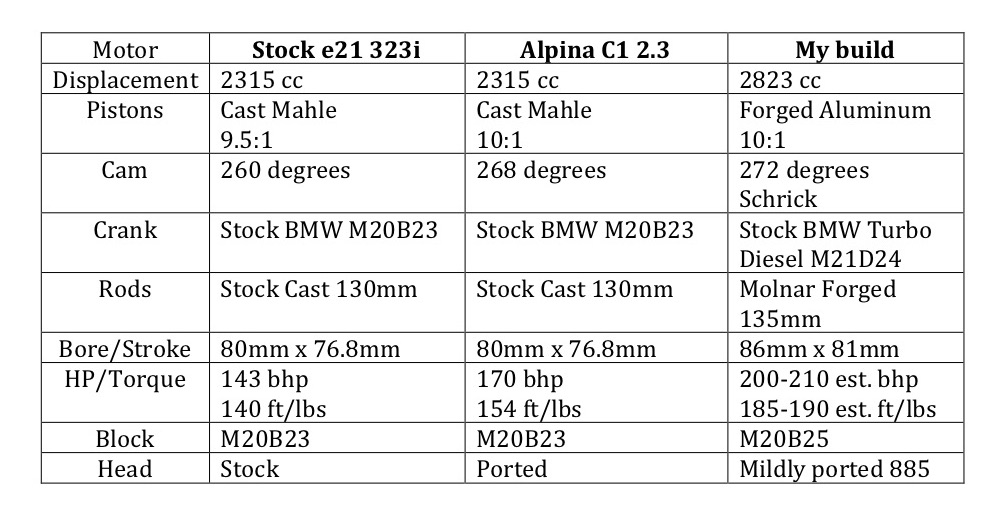

Our plan is for me to keep going up to Sacramento until we get the car to a point that it can be put on the back of a trailer, driven back down to my house where I’ll finish the work. Virtually every decision-point was vetted. Twenty-eight hundred cc displacement was chosen because I wanted to use a turbo-diesel crank (it’s a very stout crack, able to withstand the high pressures of the diesel motor) and I always kinda liked the e30 c2 2.7, based on the same crank and big bore. The pistons were an easy decision, given the crank and desire to get at least 2700cc. I didn’t feel the need for a much bigger bore and knew that several folks had successfully used a 86 mm bore on the stock 325i M20 block.

Virtually every decision-point was vetted. Twenty-eight hundred cc displacement was chosen because I wanted to use a turbo-diesel crank (it’s a very stout crack, able to withstand the high pressures of the diesel motor) and I always kinda liked the e30 c2 2.7, based on the same crank and big bore. The pistons were an easy decision, given the crank and desire to get at least 2700cc. I didn’t feel the need for a much bigger bore and knew that several folks had successfully used a 86 mm bore on the stock 325i M20 block.

For torque I used the B6 2.8 as a reference point as well. The early B6 motor put out 182 and the later 195. Mine should be in the middle as well but 185 is a safe number.

For torque I used the B6 2.8 as a reference point as well. The early B6 motor put out 182 and the later 195. Mine should be in the middle as well but 185 is a safe number. And then the drive belt and the pulleys.

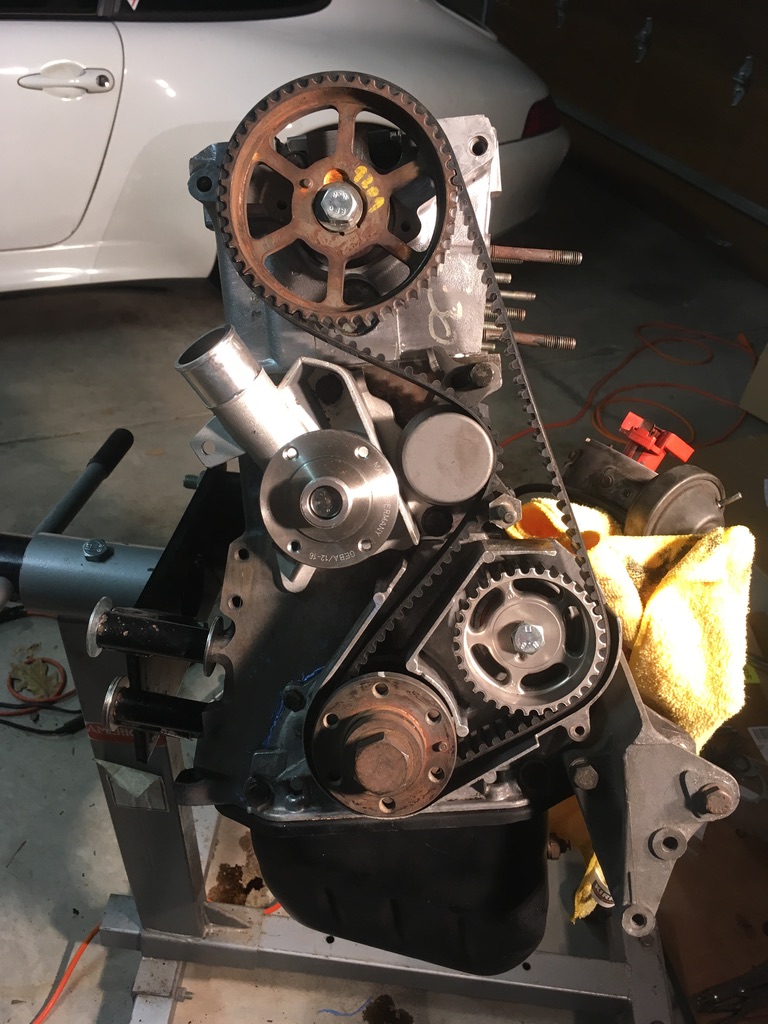

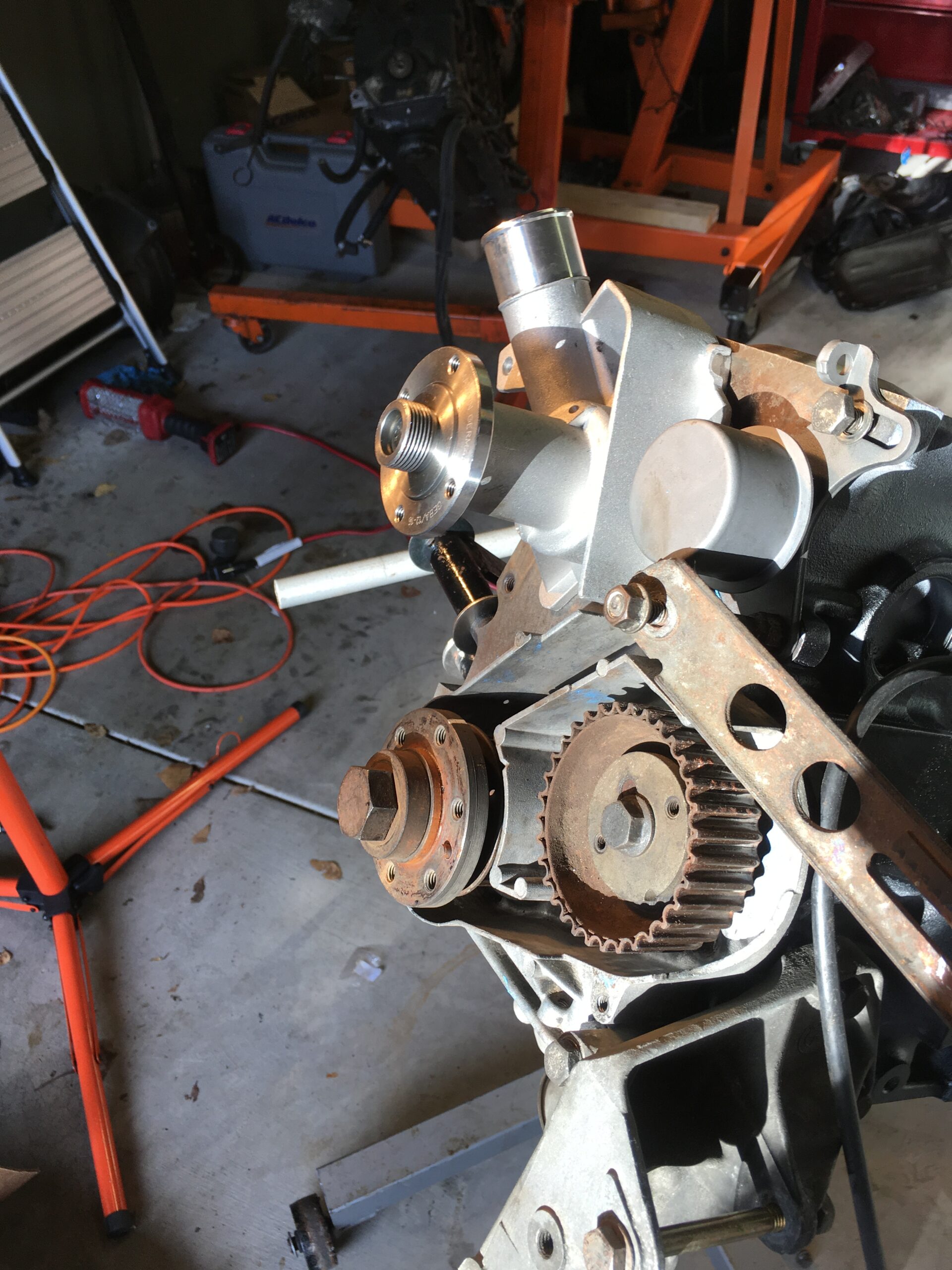

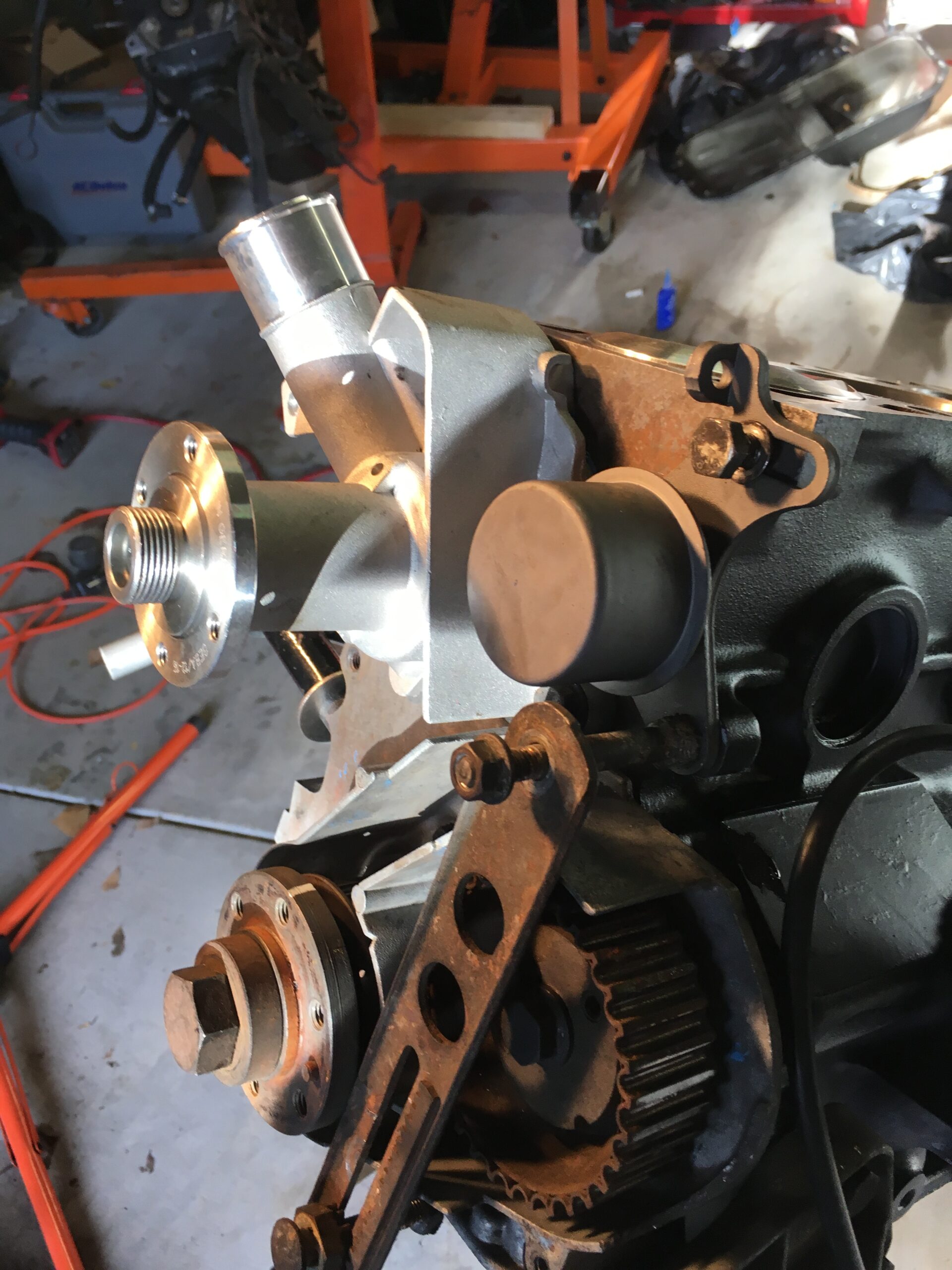

And then the drive belt and the pulleys. Then the oil pan was ready to go on.

Then the oil pan was ready to go on.

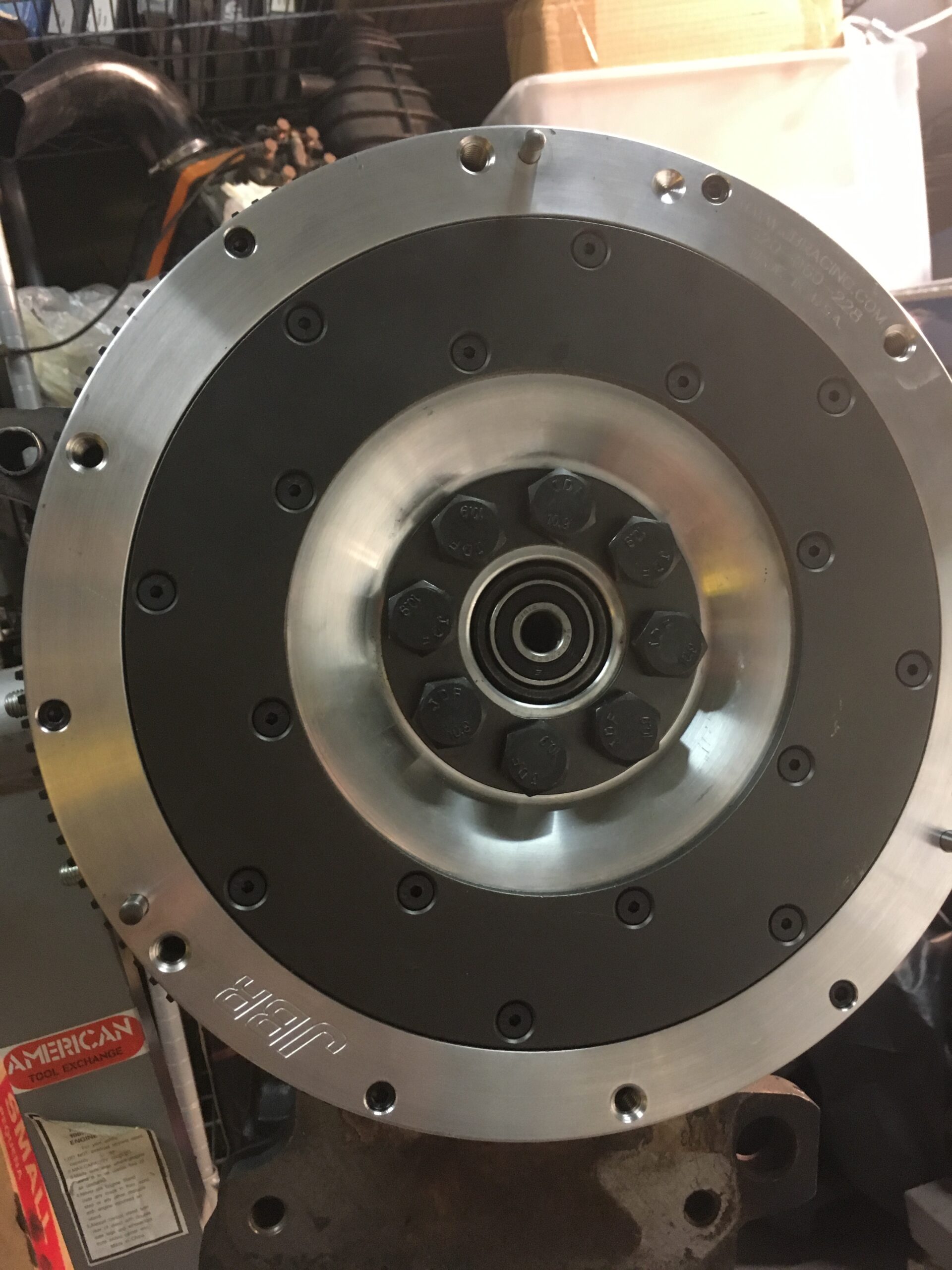

And then the rest of the rotating mass and the front covers.

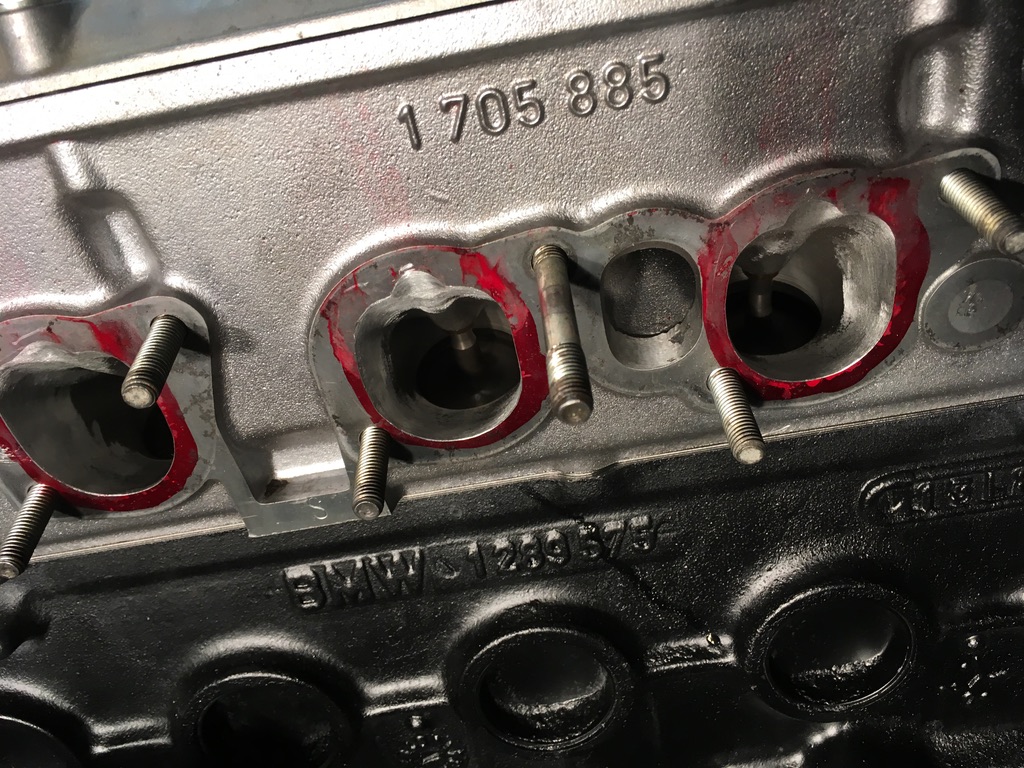

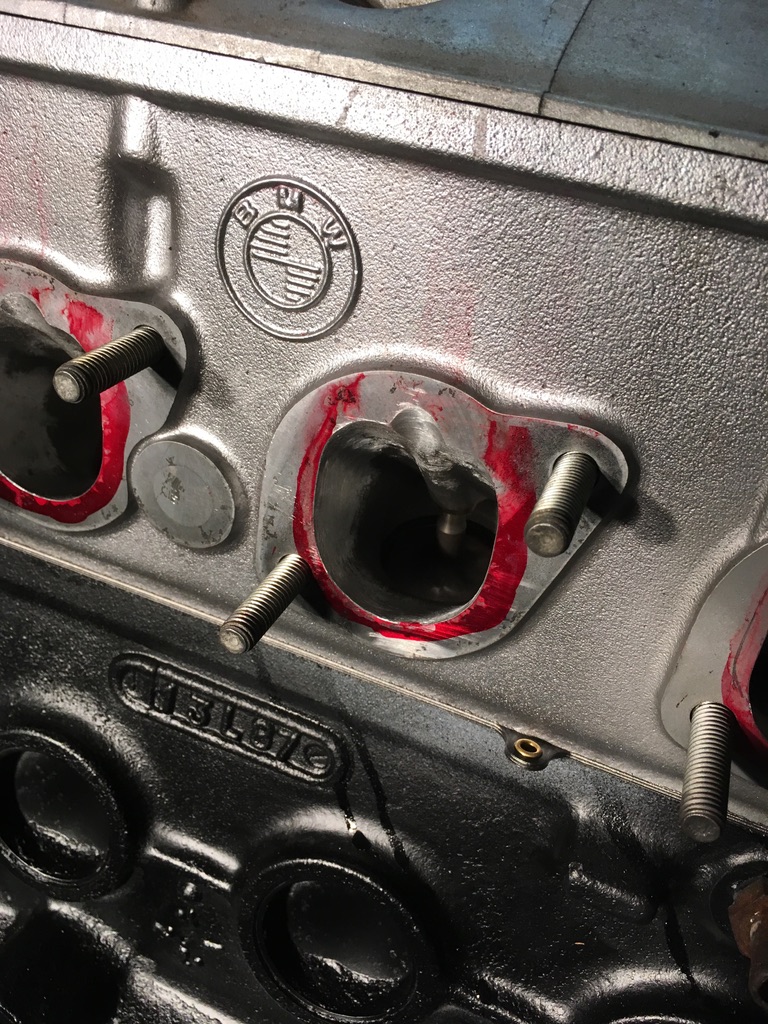

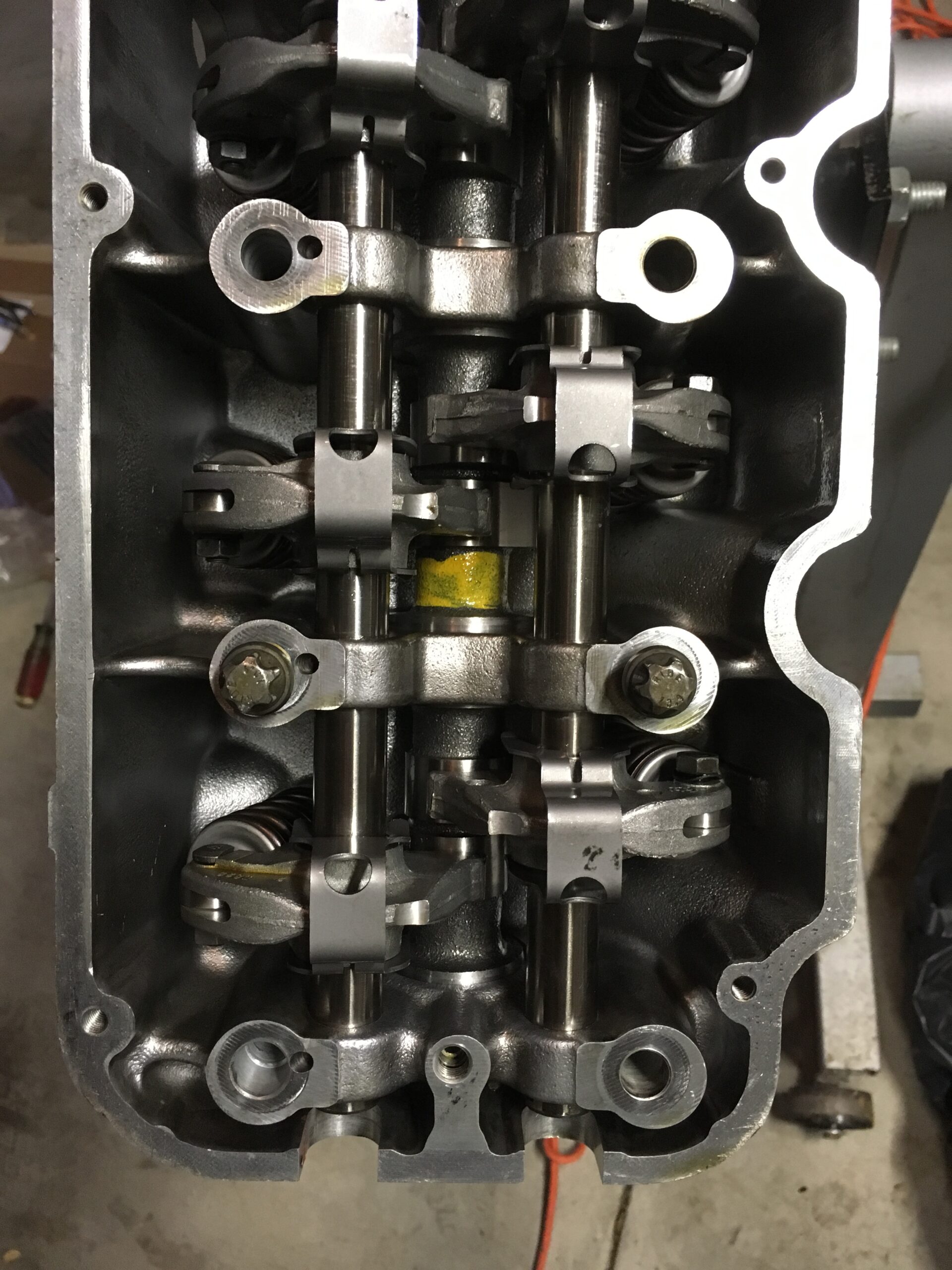

And then the rest of the rotating mass and the front covers. Once the motor was assembled, I was able to take some time to appreciate the machine work. Here, the intake ports were gasket matched to the intake manifold.

Once the motor was assembled, I was able to take some time to appreciate the machine work. Here, the intake ports were gasket matched to the intake manifold.

And visa-versa for the intake manifold.

And visa-versa for the intake manifold.  I made plans with Stu for him to bring his X5 down to my house and pick up the motor and the various parts. That meant next up for me was organizing the other parts. Got a couple or four bins of parts together.

I made plans with Stu for him to bring his X5 down to my house and pick up the motor and the various parts. That meant next up for me was organizing the other parts. Got a couple or four bins of parts together.

And put the motor on the cherry picker.

And put the motor on the cherry picker.

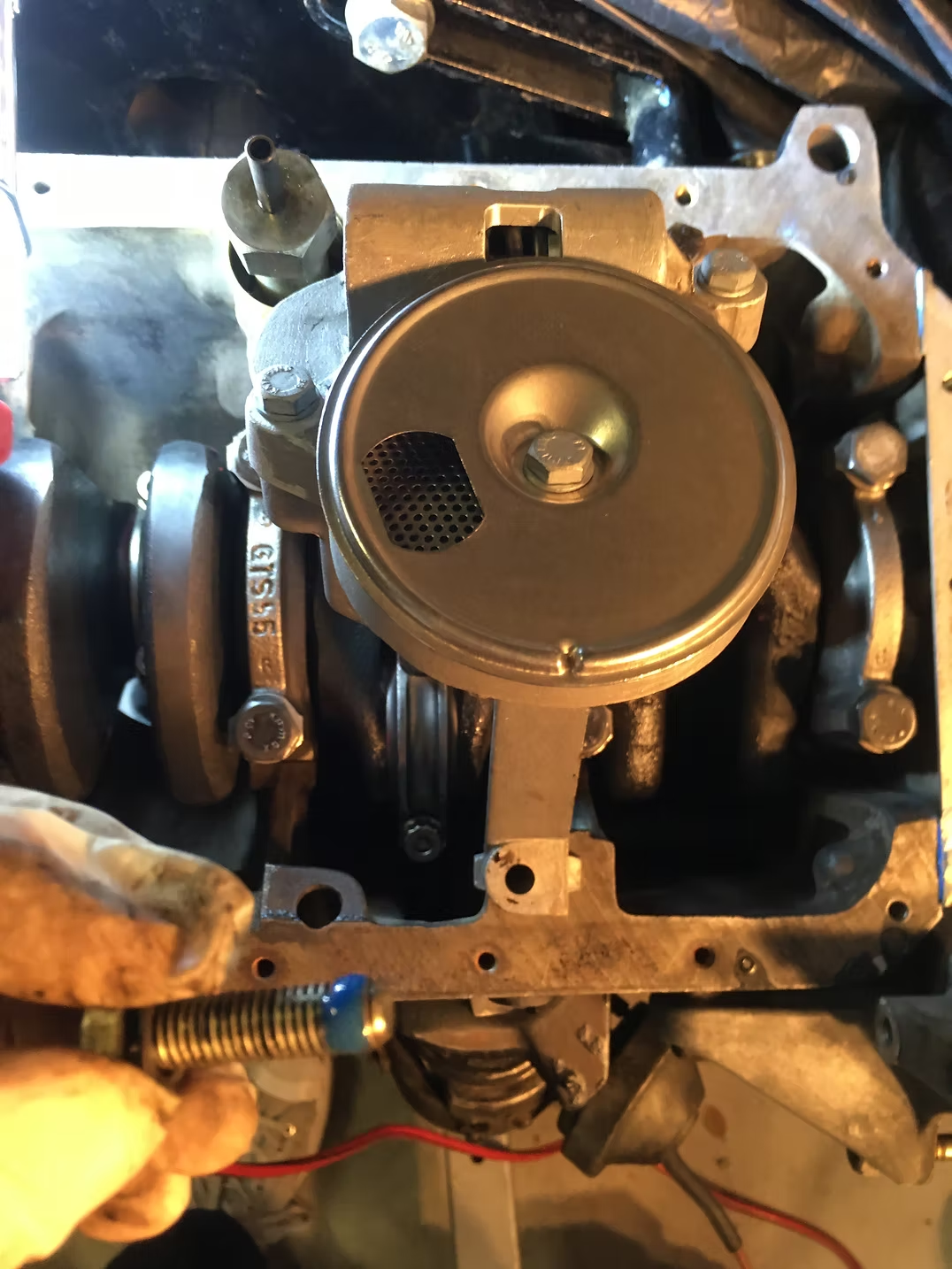

Stu came and picked up the motor late one night, and after getting it to his shop, he had a chance to look it over. After looking at the intake manifold, he asked if it was ok for him to smooth the porting out a little. Of course! He also wants to pretty up the front covers and the harmonic balancer on the front crank pulley. Why not! I’m sure these will delay the project some more, but I clearly am not making my original goal of a late August debut at Monterey, so I have another year to get everything done.

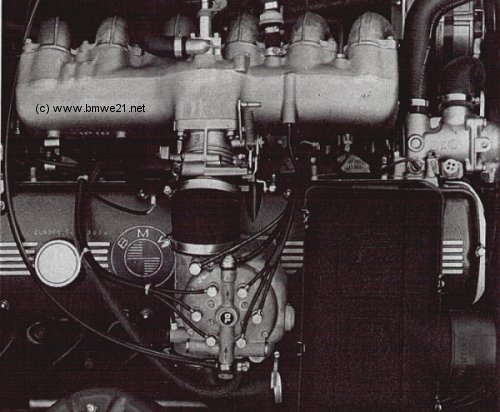

Stu came and picked up the motor late one night, and after getting it to his shop, he had a chance to look it over. After looking at the intake manifold, he asked if it was ok for him to smooth the porting out a little. Of course! He also wants to pretty up the front covers and the harmonic balancer on the front crank pulley. Why not! I’m sure these will delay the project some more, but I clearly am not making my original goal of a late August debut at Monterey, so I have another year to get everything done. When wrenching on that, something interesting was discovered. The warm-up regulator bolts to the block (on top of a manifold that has coolant running through it). When unbolting those for Stu to take to Sacramento, we found the bottom of the manifold is exposed to the sump, with a bore through the block and a nice rubber gasket to keep it sealed. Why? What does that accomplish? The m10 K-Jet doesn’t do that and we can’t figure out why the M20 does – so, is it necessary to bore out the new block? We don’t think so, but if you know otherwise, feel free to let me know.

When wrenching on that, something interesting was discovered. The warm-up regulator bolts to the block (on top of a manifold that has coolant running through it). When unbolting those for Stu to take to Sacramento, we found the bottom of the manifold is exposed to the sump, with a bore through the block and a nice rubber gasket to keep it sealed. Why? What does that accomplish? The m10 K-Jet doesn’t do that and we can’t figure out why the M20 does – so, is it necessary to bore out the new block? We don’t think so, but if you know otherwise, feel free to let me know. Next up is pulling the Alpina motor apart and figuring out what is in there and whether the head gasket is blown. Then I’ll clean it up and freshen up the innards.

Next up is pulling the Alpina motor apart and figuring out what is in there and whether the head gasket is blown. Then I’ll clean it up and freshen up the innards.

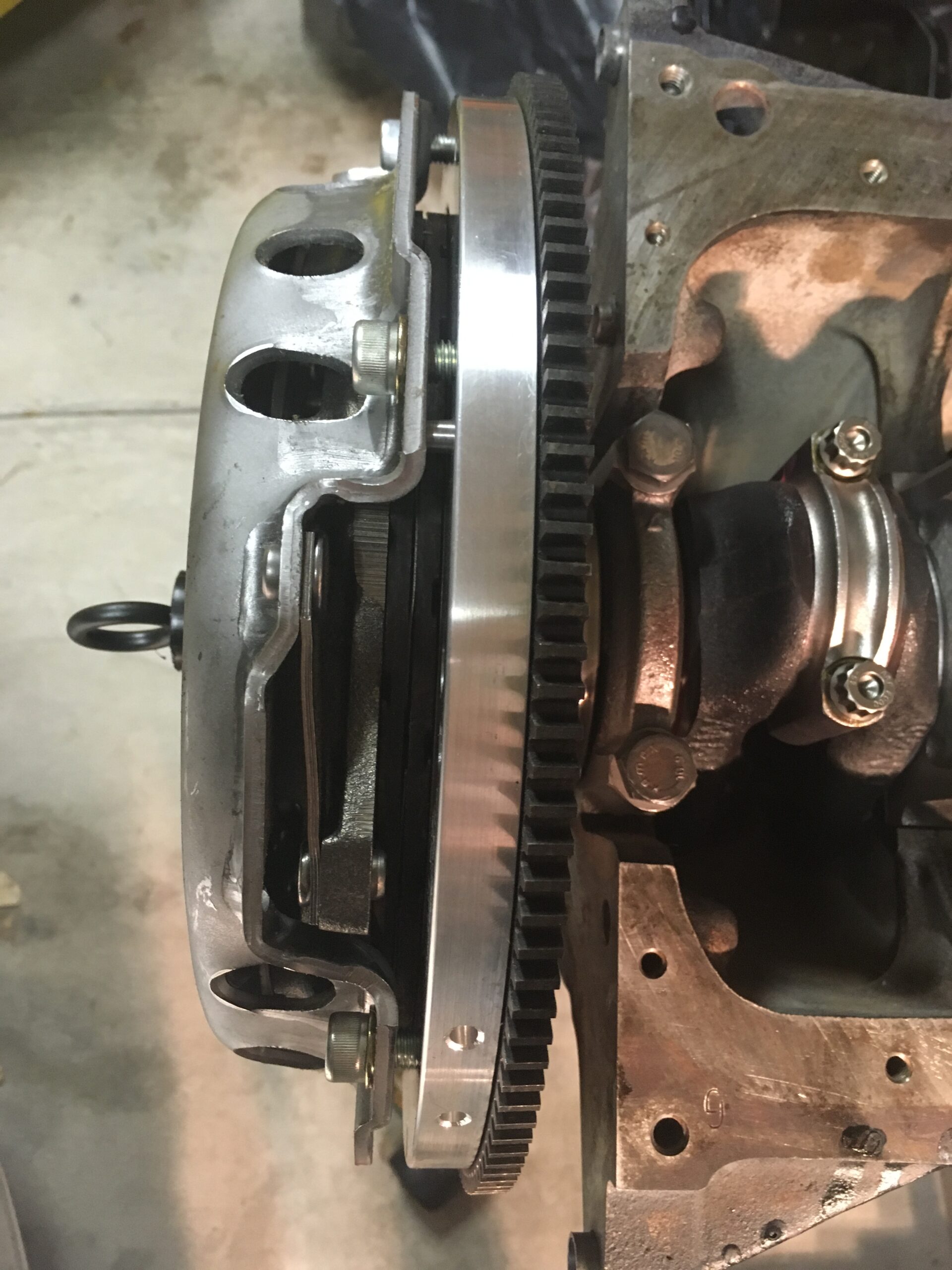

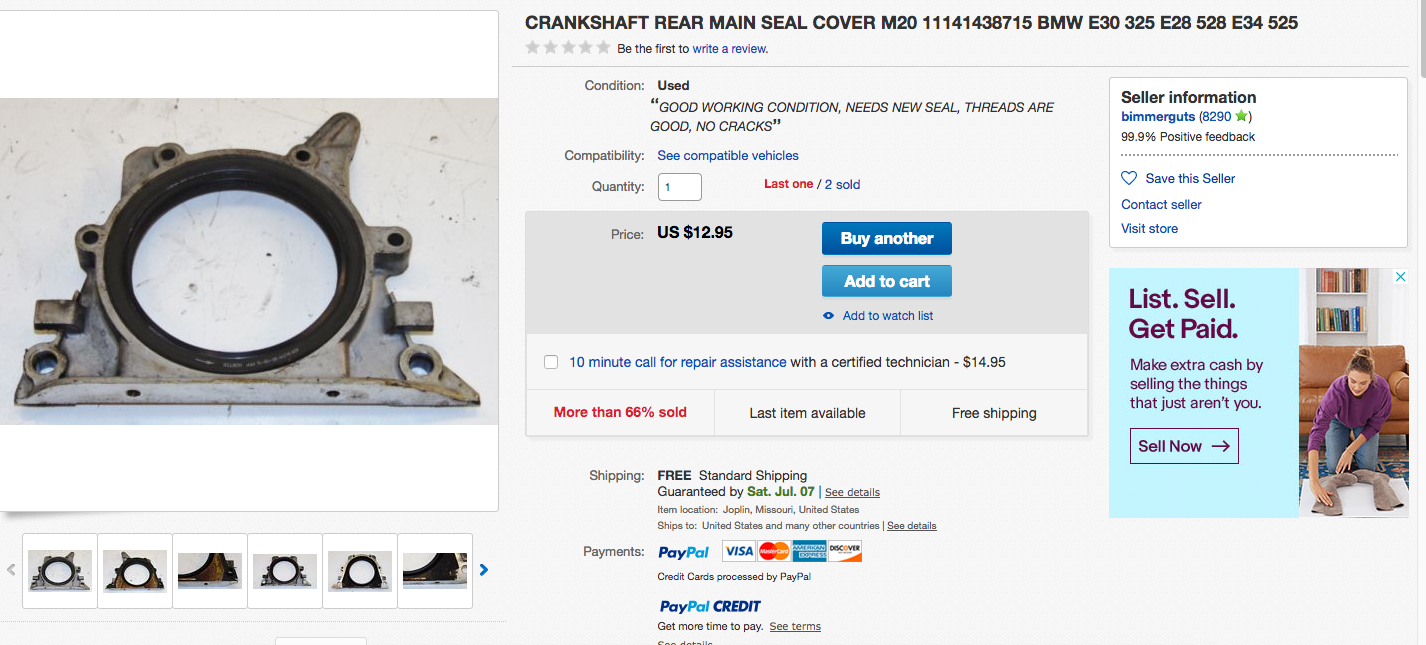

Shortly after doing that, I realized I made a bone-headed mistake and didn’t install the rear main seal nor its housing. A legitimate question: How could this happen? The best excuse I have is that I haven’t disassembled the original engine, bought a used block and that part wasn’t included – and then, in all the excitement of getting the rotating assembly together, I simply forgot about such things.

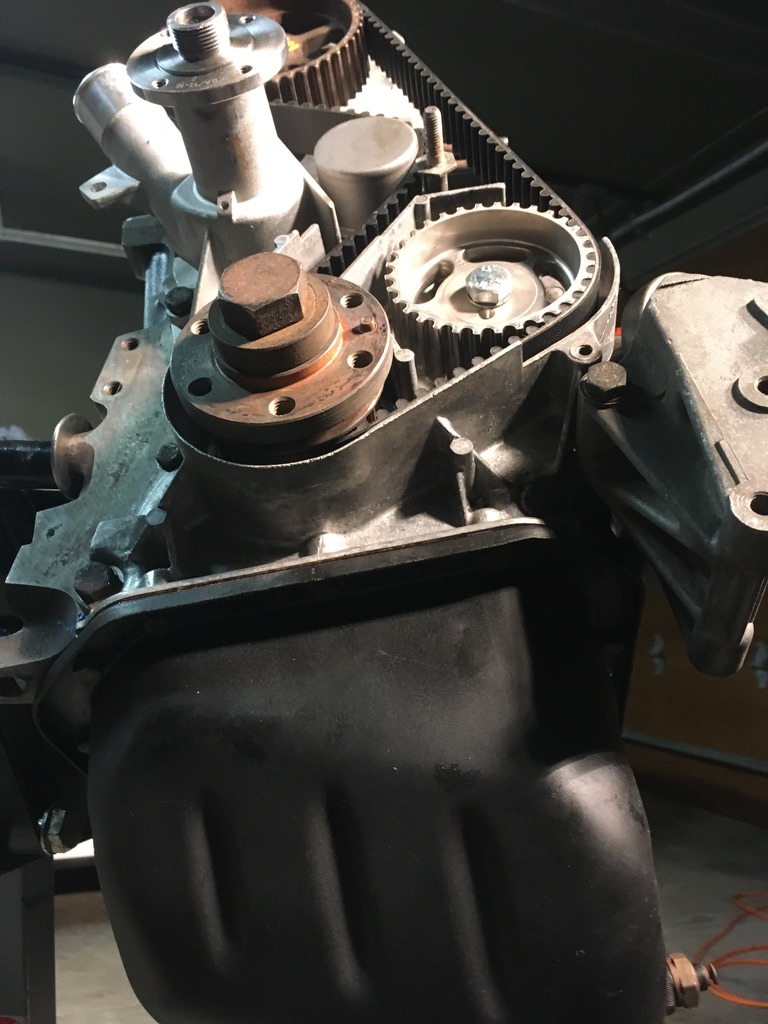

Shortly after doing that, I realized I made a bone-headed mistake and didn’t install the rear main seal nor its housing. A legitimate question: How could this happen? The best excuse I have is that I haven’t disassembled the original engine, bought a used block and that part wasn’t included – and then, in all the excitement of getting the rotating assembly together, I simply forgot about such things. Having never work on an M20 motor before – let alone built one – the next steps vexed me. Unsure of how to tackle it, I started taking the front covers and hubs around the timing belt.

Having never work on an M20 motor before – let alone built one – the next steps vexed me. Unsure of how to tackle it, I started taking the front covers and hubs around the timing belt. This went smoothly until I encountered the screws securing the intermediate shaft drive. For some reason, instead of using allen screws, BMW used standard head machine screws. Given the torque on these, one simply refused to loosen. Worse, I started to strip the head as I tried. I went into the house, had a beer, and thought about how to get that thing loosened. It came to me: An impact screwdriver!

This went smoothly until I encountered the screws securing the intermediate shaft drive. For some reason, instead of using allen screws, BMW used standard head machine screws. Given the torque on these, one simply refused to loosen. Worse, I started to strip the head as I tried. I went into the house, had a beer, and thought about how to get that thing loosened. It came to me: An impact screwdriver! Once that arrived, it was simply a matter of a few blows with the mallet, a few more, a couple more for good measure, and the uncooperative screw was beaten into submission, first barely turning but with each blow going a bit further until I was able to remove it with a normal screwdriver. The intermediate shaft drive was off and the new one on! For good measure, new screws holding the drive were ordered and installed, too.

Once that arrived, it was simply a matter of a few blows with the mallet, a few more, a couple more for good measure, and the uncooperative screw was beaten into submission, first barely turning but with each blow going a bit further until I was able to remove it with a normal screwdriver. The intermediate shaft drive was off and the new one on! For good measure, new screws holding the drive were ordered and installed, too. To get to the main pulley the main crank nut had to be removed. Simple concept but considering it’s torqued to more than 300 ft/lbs…. I puzzled on that for a while, since my electric impact wrench wasn’t strong enough. Talked to a few friends, thus further delaying progress.

To get to the main pulley the main crank nut had to be removed. Simple concept but considering it’s torqued to more than 300 ft/lbs…. I puzzled on that for a while, since my electric impact wrench wasn’t strong enough. Talked to a few friends, thus further delaying progress.

Then main pulley had to be removed and that required a puller.

Then main pulley had to be removed and that required a puller.

The rest of the front cover removal from the old motor and re-installation on the new one went smoothly.

The rest of the front cover removal from the old motor and re-installation on the new one went smoothly.

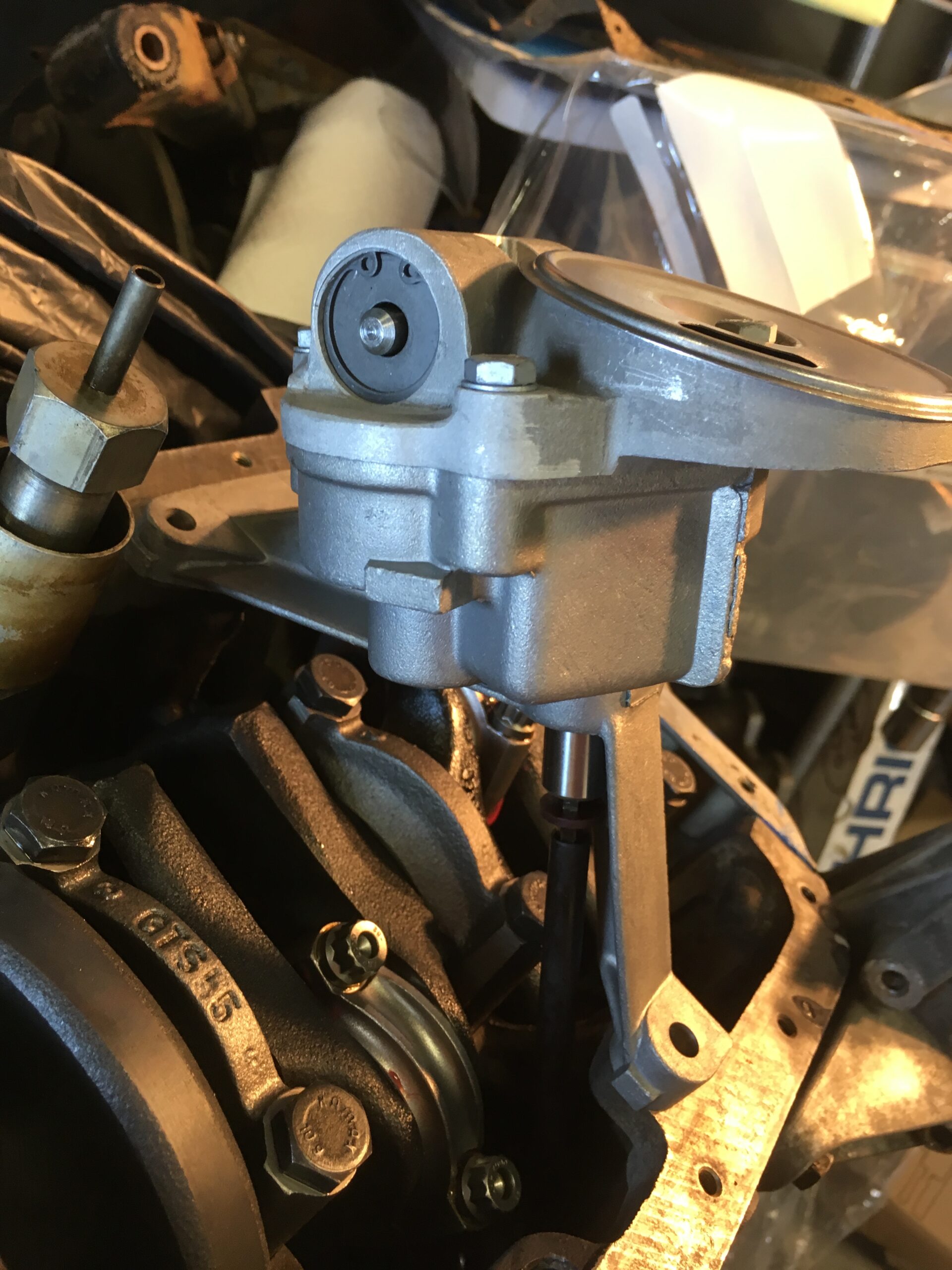

Next came the oil pump. Wait. Where is the new oil pump? Did I order one? How could I forget that? Couldn’t find one so I searched the invoices for the various parts I ordered. None included an oil pump, so that needed to be ordered. Another delay. While waiting I took the pressure relief valve off the old engine and put it on the new.

Next came the oil pump. Wait. Where is the new oil pump? Did I order one? How could I forget that? Couldn’t find one so I searched the invoices for the various parts I ordered. None included an oil pump, so that needed to be ordered. Another delay. While waiting I took the pressure relief valve off the old engine and put it on the new. Once the oil pump was in hand, I mounted it on the underside of the block. First a test fit, with the drive and then locktite on the bolts. But, since I never worked on an M20 before I didn’t know how the pump (and distributor) was driven. Hence my introduction to the intermediate shaft and the drive off the belt. Some momentum was building, after all the delays, but it was still over a month since the last update here.

Once the oil pump was in hand, I mounted it on the underside of the block. First a test fit, with the drive and then locktite on the bolts. But, since I never worked on an M20 before I didn’t know how the pump (and distributor) was driven. Hence my introduction to the intermediate shaft and the drive off the belt. Some momentum was building, after all the delays, but it was still over a month since the last update here.

The distributor went in.

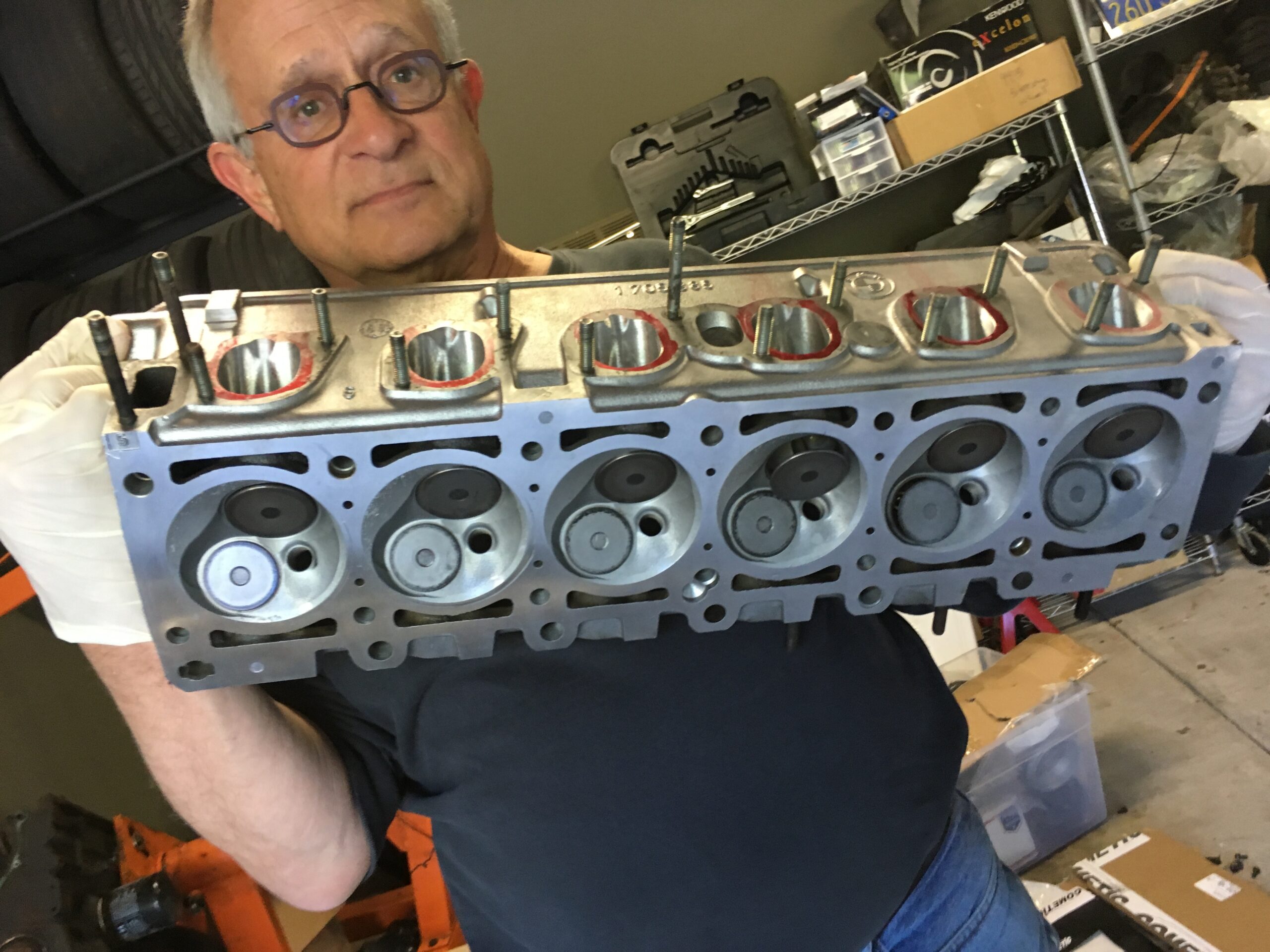

The distributor went in. The head gasket on the block. The head gasket itself is unusual, a metal one that had to be custom made because of the boring out of the block.

The head gasket on the block. The head gasket itself is unusual, a metal one that had to be custom made because of the boring out of the block. The head on that (thanks Frank for the help).

The head on that (thanks Frank for the help).

But, wait, where are the washers for the head bolts? Nowhere – not ordered. Another delay. Calls to the local BMW dealers showed none in Northern California, so another parts order and another delay.

But, wait, where are the washers for the head bolts? Nowhere – not ordered. Another delay. Calls to the local BMW dealers showed none in Northern California, so another parts order and another delay.